Richard Ayoade’s 2010 film Submarine was a warm, charming, stylish and frequently hilarious story of adolescent awkwardness that this particular writer has been recommending, sharing and gifting since falling head over heels for it on release. It’s not an uncommon response to it, one understands. So, as one would gather expectations of his second feature, The Double, were understandably high – and justifiably so, it transpires.

The Double is an altogether darker affair than its predecessor and it’s no wonder - the source novella was written by Fyodor Dostoevsky, an author that (while no stranger to humour) isn’t renowned for his carefree jottings on the lightness of being. ‘Kafka-esque’ would have doubtlessly been splashed all over the reviews were it not published over forty years before the Czech existentialist’s birth. That should not suggest an absence of humour of course – quite the opposite. The film is intense, oppressive and intermittently grim, but it is also very funny.

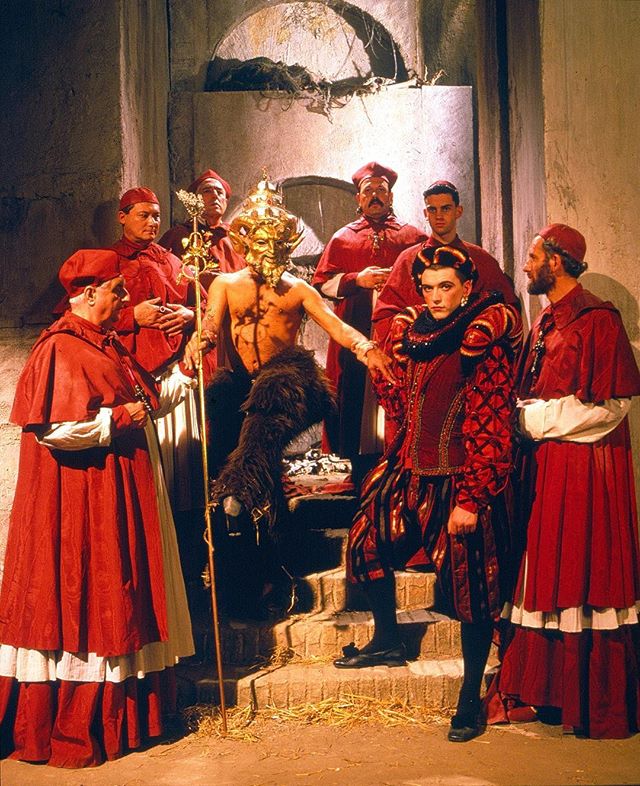

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo credit: Dean Rodgers

The set-up itself is a wry smile of a premise. The protagonist (Simon James) is a nobody - a hopelessly meek, wan, anonymous, unmemorable office worker with a perennially unrealised crush on a co-worker; one day, an employee from another office transfers to his and is an instant hit – not only is his name James Simon, but he is everything Simon James is not (brash, confident, well liked, manipulative, lazy, dishonest); he’s also Simon James’ exact double, and nobody notices except them. Needless to say, the chain of events that follows brings Simon James to the brink of his sanity. Jesse Eisenberg plays both Simon and James masterfully, to the extent that one even forgets that the two characters interacting are, well, the same person. Furthermore, Eisenberg makes Simon James very much the subject of our identification, our empathy – in lesser hands, we wouldn’t care, or not as much anyway.

The setting for the film is familiar yet enigmatic. The location is unknown (the prevailing language is English; American, Australian, English, Irish and Welsh accents are all presented without remark), it could be the future or the past; it’s certainly a dystopian urban permanocturnal hinterland of lunatic bureaucracy and emotional retardation. The lack of a specific setting links it to Submarine (‘80s-ish with modern details) but (alongside many other films and filmmakers that employ this trick so well – most particularly Wes Anderson) also to Terry Gilliam’s classic Brazil; in particular, they both present a world in which progress stopped in some ways during the ‘50s yet continued in others. It could be distracting but it moreover serves to aid a fuller sense of the absurdist reality that could accommodate this strange and entrancing tale.

For all that the palette may have shifted somewhat (‘realism’ versus ‘fantasy’, bluish tones with primary splashes versus washed out greens and greys), Ayoade has already established a filmmaking language of his own. This is not to say it lacks obvious links to other films or works, far from it, but he does already exhibit a distinctive voice, a rare achievement. The Double stands up to analysis by itself, for all its narrative has a certain cultural shorthand (Chuck Palahnuik certainly must have read this particular Dostoevsky) and, as such, an underlying familiarity. It inhabits a world of its own - partly ours, partly someone else’s – and as with the most effectively realised dystopian worlds, one is both overtly repelled yet covertly seduced. This duality applies to The Double (how bad can a place in which Shin Joong Hyun is the pop star du jour be?), but one is unlikely to be left in two minds by The Double itself.

Ayoade has got a hard job following himself (again).

Andrew R. Hill