Austrian director Michael Haneke is notorious for an unflinching and uncompromising approach to the violent and the taboo. As Erika Sella finds, Haneke's eye is no less unyielding in his new film as he tackles inescapably universal themes: ageing and Amour...

Emmanuelle Riva as Anne. Image courtesy of Artificial Eye.

“My films are intended as polemical statements against the American ‘barrel down’ cinema and its dis-empowerment of the spectator. They are an appeal for a cinema of insistent questions instead of false (because too quick) answers, for clarifying distance in place of violating closeness, for provocation and dialogue instead of consumption and consensus.”

Michael Haneke’s films have always inspired debates amongst critics and audiences. Funny Games (1997) sparked fierce discussions about the portrayal of violence on screen. At the time of its release, Mark Kermode (quite the detractor) remarked: “Rarely has a film-maker exercised such perverse precision in his desire to torment an audience for whom he clearly harbours unbridled contempt”. His pessimistic view of the human condition and of society as a whole was evident in both The Piano Teacher (2001) and The White Ribbon (2006). The latter was, according to the director, ‘a study in the roots of evil’, dealing with a group of young children “who absorb the full consequences of the ideals preached to them, and who go on to punish those who have enforced these ideals without living by them”. The White Ribbon was interpreted by many to be about the origins of fascism (specifically Nazism), but Haneke, who usually refuses to offer simplistic interpretations of his own work, has always maintained that the film’s theme was much more universal than that.

Given that his films are usually been described as “endurance tests”, it was intriguing for me to see how he would approach a subject like enduring devotion and its relationship with physical decay and death.

Amour tackles undoubtedly sombre yet

emotionally charged and universal matters.

Georges (Jean-Louis Trintigant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) are retired

music teachers who still enjoy life to the full. Their union can be described

as blissful - they are both intellectually active and still relish each other's

company. They have a middle-aged

daughter, Eva (Haneke regular Isabelle Huppert), who lives abroad and seems (at

least superficially) distant.

Anne suffers a series of strokes that slowly debilitate her, transforming her from a vigorous, lively woman to a bed-ridden, near-mute individual. Her illness turns the couple's world upside down: Anne refuses to be taken to hospital and Georges decides to care for her at home. Eva, appalled by her condition (“She’s speaking gibberish … what’s next?"), suggests that she could be taken to a home. Her father is horrified at the advice given and (perhaps not in an entirely deliberate manner) proceeds to exclude his daughter from the apartment they live in.

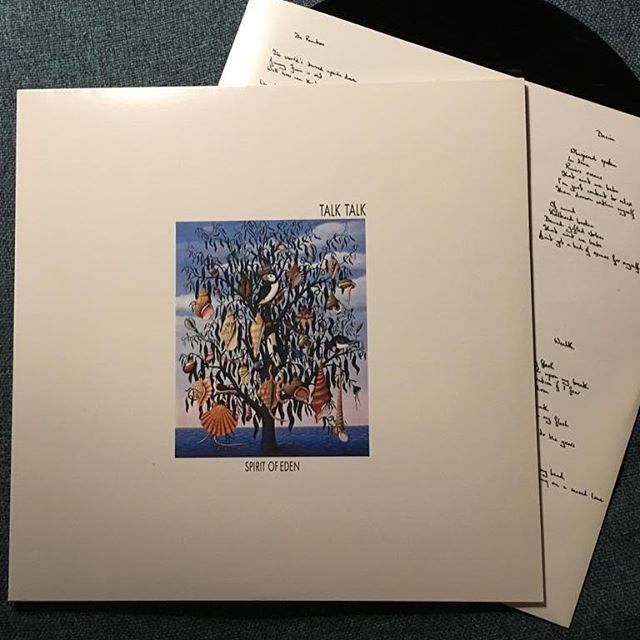

Space is really important in the film. Amour is shot almost entirely within the confinements of the couple's Parisian flat: details such as their records, books, paintings and baby grand piano are fundamental to their dynamic. Music has got a healing, almost redeeming quality in the film. Georges seeks comfort in Bach's Cantatas; when he remembers his wife before her stroke, he thinks of her playing the piano. The couple try to sing Sur Le Pont D'Avignon together as an exercise to help with Anne's speech. In a similar way, literature provides some relief in the early stages of the illness. Later in the film, an old family photo album (containing actual photos of both actors in their youth) prompts the comment: “C'est belle, la vie”.

This is their precious (and crumbling) world, and it's easy to see why Georges becomes obsessively protective of it. It's no coincidence that the couple discuss their fears of being burgled early on in the film.

Yet the undeniable beauty and tenderness of their

relationship are always undercut by the impending tragedy. Anne's inevitable

disintegration is a tough watch. Georges’ words to his daughter (who has been

literally locked out of her mother's bedroom) - “None of this deserves to be

seen” - ring a bell with the audience: Haneke's typically austere style renders

the depiction of the illness unflinching and devastating. We see Anne wetting her bed, and later

showered by a nurse and force-fed by her husband. She can no longer speak. She only manages the

word “mal”, which could be translated as both “it hurts” and “evil”.

The ultimate intruder (terminal illness, death)

has come into their life and there is nothing anyone can do about it. Haneke keeps reminding his audience of this

through recurrent metaphors. Georges has to deal with a pigeon trying to enter

the flat (twice) and later has a nightmare where he is attacked after he

wanders outside thinking he has heard someone trying to break in. His words “Is

anyone there?” are ambiguous: he is scared of what is about to happen to his

wife (and himself) or is his call a desperate (and maybe even nihilistic) one?

As a spectator I felt anguished, moved, but also incredibly powerless.

Haneke is asking us once again to witness human suffering. Anne's illness clearly does deserve to be seen: the film poses a lot of difficult question about mortality and the role companionship when faced with pain and the collapse of everything we know. The director is still provocative in this sense, but with Amour his vision has been tempered by a newfound compassion. It is a particular strand of tenderness, present in small details and completely unsentimental. It is an attitude exemplified by Georges’ horrified recounting of a friend's funeral (where a relative plays The Beatles' Yesterday on a tape recorder); Haneke refutes any cheap sentimentality and instead delivers a film that explores the very core of that much-discussed sentiment, love.

'Amour' is on general release in cinemas across the UK now.