Vertigo Sea may be overwhelming at times, but a deep dive into this immensely beautiful and mesmerising work is worth your time. Take a deep breath...

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

John Akomfrah’s work has long dealt with issues pertaining to migration, postcolonialism, multiculturalism, cultural amnesia. Born in Ghana in 1957 to parents involved in the country’s independence movement, moving to London at the age of four and coming of artistic age during the peak of Thatcher’s destructive reign (co-founding the Black Audio Film Collective during this time), Akomfrah is better placed than most to do so. Across its 48-and-a-half minutes, Vertigo Sea continues to explore these themes but expands the outlook into ecological concerns.

Vertigo Sea extrapolates on a career-long exploration of the montage, a form, Akomfrah has explained, “Allows the possibility of reengagement, of the return to the image with renewed purpose.” If Handsworth Songs (1986) is rightly seen as a landmark in the montage-laden essay film genre (if it is its own genre), Vertigo Sea explodes it into a whole new realm.

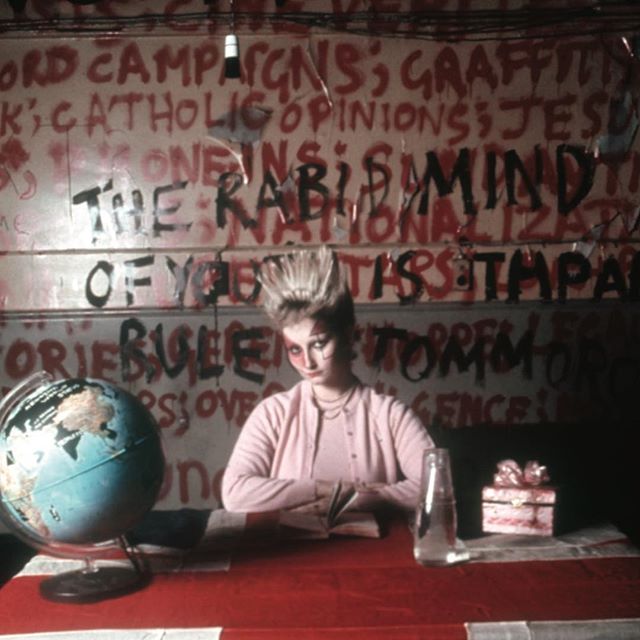

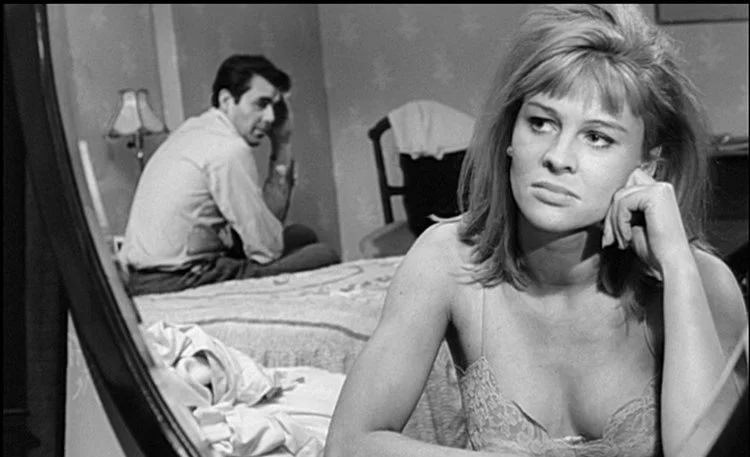

Specifically filmed tableaux populated by often lonesome figures in archaic costumes and abstractly dressed landscapes mix with a heady brew of archival footage (a large proportion of which is drawn from the BBC Natural History unit) and photographs. Akomfrah is something of a master of the collation and transposition of archival material; as he has said, “It’s important to read images in the archive for their ambiguity and open-endedness.” As has been much discussed elsewhere, this bricolage format seeks to return some agency to its subjects and its viewers, by letting both parties exist without directing either how to speak or how to respond – of course, there is a great deal of mediation between Akomfrah’s film and the audience, but at no point does he didactically beat you about the head.

A deep Derek Jarman-esque blue encompasses you in Vertigo Sea’s opening moments, the title in an antiquated font, then the subtitle: Oblique Tales from the Aquatic Sublime. The blue immersion recurs periodically throughout – paragraph or page breaks, perhaps. Both the title and the subtitle are, at a surface level, appropriate. At times, the film can certainly feel overwhelming, both as a visual spectacle and in its occasionally terrifying, often beautiful, scope - sublime in the truest sense, then.

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

You feel the vertigo - dizzy, giddy and unstable as you drift atop and peer down into a vast ocean of history, a miasma of memory and forgotten people, animals, acts, murders, massacres, slaughter, disaster. Spread across three screens, often disparate in their depictions, one cannot help but be reminded of the triptych – that form perhaps better than any other to encapsulate both the beauty of Creation (as in depictions of the Virgin and Child) and of man’s inhumanity to man (the Crucifixion). Perhaps more than any other triptych, one could think of Hieronymus Bosch’s disturbing and compelling The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1490 – 1510) (referred to explicitly in Akomfrah’s 2012 piece Peripeteia), if nothing else than for their shared density. On one screen you may have a submerged whale or a lonesome polar bear, on another a thunderstorm or melting ice caps, on another a photograph of a victim of Pinochet’s regime or a dramatized recreation of murdered black bodies washed upon the beach; on another a mysterious Caspar David Friedrich-esque Rückenfigur silently looking out over a Romantic landscape or hooded and half-submerged, looking out to the sea like one of Anthony Gormley’s unsettling Another Place sculptures.

The vertiginous sensation is scarcely ameliorated by other textual levels, the various voiceovers that boom out across the ambient soundscape – Herman Melville, Virginia Woolf, Heathcoate Williams, Friedrich Nietzsche, BBC news reportage – as well as written quotes from Jorge Luis Borges, Edwin Morgan and Fred D’Aguiar (and these are only some examples of those quoted).

We hear a Nigerian migrant’s account from 2007 of brutality adrift in the Mediterranean, abandoned by the pilot of the boat carrying the human cargo he once was. Then, the repentant former slave trader and abolitionist, the Reverend John Newton (1725 – 1807) intones, “Why do I speak of one child, when I have heard of over a hundred men cast into the sea?”, words from 1787 on the Zong massacre of 1781, where 133 slaves were thrown overboard for insurance purposes. The equivalence that is being presented is clear but not lacking in nuance, just one of many associations at work at any given time in Vertigo Sea. The constant juxtapositions occurring across these different forms can draw you into any number of interpretative whirlpools.

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

Newton may have come across the Zong massacre in an account by Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745 – 1797), an Igbo slave who bought his freedom and became the first black person to explore the Arctic, the first black employee of the British government and a bestselling author with his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789). Equiano is one of the mysterious Romantic figures, gazing from mountaintops across great chasms, resplendent in a tricorn hat and red jacket, every bit the 18th-century confronter of the sublime. One cannot help but feel Equiano is watching everything, seeing everything that is happening in this film. He transcends the gap between the African and the European, the captive and the master, the ‘noble savage’ and the refined intellectual, the imperialist and the abolitionist. He refutes the simplicities of these sometimes offensive reductions and dualities. Is he waiting for something, as he looks at the clock in his hand? Waiting for everyone else to catch up?

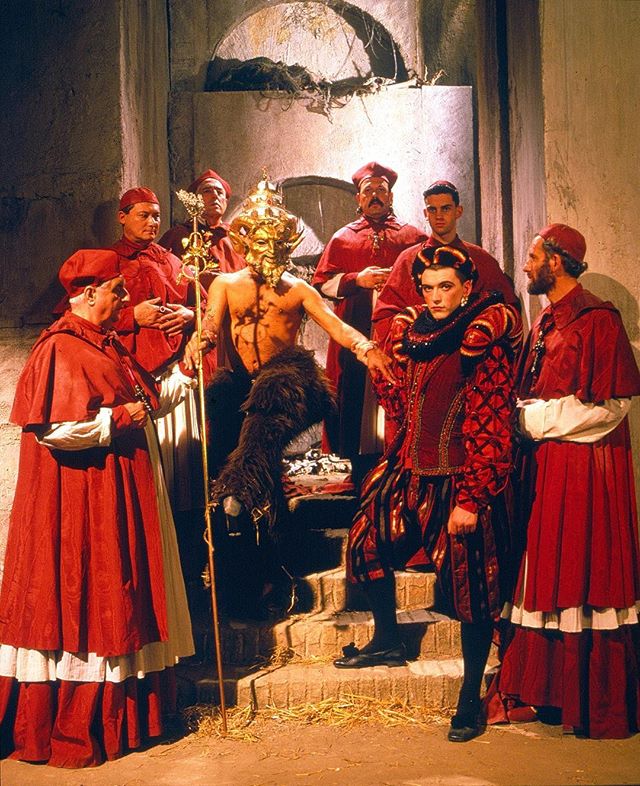

Someone else who appears to be waiting is the old man in black and white, who recurs with increasing frequency toward the end of the film. As with so many of the other images or quotes in the film, the viewer cannot necessarily be expected to know what or who is being represented, but this is Béla Bartók, as portrayed by Boris Ranevsky in Ken Russell’s 1964 Monitor episode about the composer. He looks frail, completely lost in thought, sitting uncomfortably as if expectant of an arrival or an impending cataclysm, alone in a Spartan attic room, little but a gramophone for company. Bartók fled his native Hungary, an Axis member, having been a committed antifascist. Exiled to an unfamiliar place, feeling stripped of purpose and thus of agency, he hides in his room, overwhelmed by confrontations with the outside world – an outside world that appears hostile, but is not innately so. He is a political migrant, a refugee of war, not unlike those who have been forced to flee to Europe in recent years. He escaped the grim fate such those critics of Pinochet had, thrown into the sea from helicopters in the middle of the night, or that of the similarly treated crevettes Bigeard (‘Bigeard’s shrimps’) of the Algerian War – all further ghosts of the deep whose photographs and stories haunt Akomfrah’s film. Bartók’s troubled, distant gaze is obvious, whether you know who he is or not, and the chances are you don’t. You cannot help but ask yourself – what is he haunted by? A place he has left behind? An awful deed? Or an idea he wants to leave behind, but will not leave him? Bartók fought an ideology, but had no choice but to run away.

Europe’s darkest chapter also resonates subtly through an early part of Vertigo Sea, when you hear a quote from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, a text that introduced the Übermensch to the world – a concept that, rightly or wrongly, leads almost everyone to the horror of the same ideology that drove Bartók to America. “In the end one only experiences oneself.” While there is no doubt a lot of truth in such an assertion - that one’s whole existence is defined by one’s unique, subjective experience of the world - it seems that Vertigo Sea refutes this somewhat solipsistic perspective.

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

Akomfrah has said that the film was partly sparked off by “the realisation that everything overlaps at some profound level, that the great shifts in human progress that are made possible by technology can also cause the profoundest of suffering.” The idea that our world is a complex, interwoven tissue is fairly starkly represented by the form of the film alone – the collage (of sorts) across the three screens of the various images mentioned already. The connection between the perilous migrations and human abuses that have transpired over the last few centuries is perhaps more obvious than that between the aforementioned and the abuses that have happened and are happening to wildlife and the environment. But Akomfrah’s places them next to each other, suggesting to the viewer that there must be some connection or connections to be made.

Daisy Hildyard’s recent book The Second Body (2017) has a certain kinship with Vertigo Sea. Early in her extended essay, Hildyard writes “There is a way of speaking which implicates your body in everything on earth. Dead whales have something to do with you…the freak storm and the changing seasons are consequences of actions performed by your body. Meanwhile, in the human world, there are car bombs going off in Baghdad every day.” Elsewhere: “[Y]our first body is the body you inhabit in your daily life”, and the ‘second body’ of the title is a product of climate change which “…creates a new language...It makes every animal body implicated in the whole world.” In true essay form, Hildyard’s book drifts away into something more personal which seeks to prove the thrust of the opening chapters, but its core position is a powerful distillation of this contemporary feeling that we do not just affect our immediate surroundings.

Hildyard’s concept of the ‘second body’ appears to be heavily influenced by Timothy Morton, whose work also informs Akomfrah’s recent six channel installation Purple (2017). Morton posits that ‘hyperobjects’ such as global warming mean “changing our relationship with other entities in the universe – whether one of animal, vegetable or mineral – to one of solidarity. If we fail to do this, we will continue to wreak havoc on the planet…we cannot transcend our limitations or our reliance on other beings. We can only live with them.” This language, most particularly the use of the word ‘solidarity’, certainly chimes with the Marxist over/undertones of much of Akomfrah’s work.

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

The dead whales that Hildyard mentions appear frequently in Vertigo Sea. There are frequent images of whaling, not just the harpooning of whales, but the scoring of enormous walls of flesh, fat and blood and entrails pouring across the decks of ships and whaling ports, men in oilskins wading through the slurry, the beautiful leviathans reduced to material substances. The acts these men perpetrate before us are reprehensible and difficult to watch – but why did they do it? It wasn’t a hobby. Whalers spent long stretches away from home for poor pay, working in unpleasant and frequently dangerous conditions. In short, the primary driving forces behind these acts was the pursuit of money – Capitalism.

Why were slaves kept (and killed)? To produce goods that could be sold (capital). Why does the Middle East continue to be a hotbed of turbulence, strife and conflict? Oil (capital). Much of the African continent is a disaster due to the legacy of colonialist rapacity for land (capital) and natural resources (capital), manifested through infrastructural and literal impoverishment, violence and oppression - the continuation of these disasters is the capitalist (i.e. neo-imperialist) rapacity for much the same things, entrenched and amplified further by enormous international debt (capital).

And where do they come from, these desperate men, women and children that are deemed ‘rats’ and ‘cockroaches’ that drown and half-drown in the Mediterranean to (apparently) beat down our doors? You know the answer. And who is responsible? If you don’t know by now, then you ought to. Just because we know now that something was wrong (whether that something is whaling or slavery), doesn’t mean that such violence cannot or does not continue in renewed forms.

In a simple visual argument, the cause-and-effect nature of the most barbaric capitalist impulses is shown thus: the flesh of a whale is scored open on one screen; the ocean floor breaks with a tectonic fissure on another; then broken, disintegrating ice caps.

© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Lisson Gallery/Arnolfini.

The first sound we hear in Vertigo Sea is that of a ticking clock. Clocks are all across the film’s landscape, whether spread out over beaches (as in Ken Russell’s Bartók Monitor) or in Equiano’s hand. Clocks tell us not just what time it is, they tell us what time has expired (and so, implicitly, what has passed). They also tell us what time is left. Clocks are everywhere. The past is everywhere, ticking away. Signs of time, what time has passed, what time is left. And how much time is that? You can cover the beach with clocks, but it won’t stop the tide coming in.

Vertigo Sea ends in the shimmering swell of an open orchestral chord. Among other images, a boat is trying to save a whale from beaching itself, rather than trying to kill it; back to that deep blue, the credits, and slow fades in and out of monochrome photographs of victims - ghosts of our shared histories, shared mistakes, shared violence, shared regrets, shared responsibilities. We are changing our attitude to this planet, to this ecosystem, this planet that we all cannot help but inhabit – but have we changed it soon enough? And can we say the same of the way we treat one another?

There are no answers here per se, merely nudges toward lines of thought, discussion and, perhaps, action. As Akomfrah himself as said, “Art can pose problems in unique ways, allowing for other meaningful dialogues. It’s about proposing, not imposing. At its best, it’s a two-way conversation, a dialogue with the political.” The multivalent elements of Vertigo Sea jostle about before us, (as Akomfrah would have it) ‘talking to each other’ with energy, sadness, anger, quiet optimism. You can choose to converse with this work as much as you wish - paddle as shallowly or dive as deeply as you like; but when you surface from this immensely beautiful and mesmerising work (slightly dazed, giddy, really quite breathless), there can be no doubt that each and every one of us have very important dialogues to conduct - with our ghosts, with our ecosystem, and with each other.

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea screens at Talbot Rice Gallery until 27 January; Akomfrah’s multimedia installation At The Graveside of Tarkovsky is also on display.

Andrew R. Hill

Bibliography

Carey-Thomas, Lizzie. Migrations: Journeys in British Art. Tate, 2012.

Hildyard, Daisy. The Second Body. Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017.

Akomfrah, John, director. Handsworth Songs. Black Audio Film Collective, 1986, http://www.ubu.com/film/bafc_handsworth1.html.

Akomfrah, John, director. The Stuart Hall Project. British Film Institute, 2013.

Akomfrah, John. Why History Matters | TateShots. Tate, 2 July 2015, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/john-akomfrah-9259/john-akomfrah-why-history-matters.

“Exhibition Guide: John Akomfrah: Vertigo Sea.” Arnolfini, 2016, https://www.arnolfini.org.uk/whatson/john-akomfrah-vertigo-sea-1/JohnAkomfrahVertigoSeaExhibitionGuide.pdf.

Austin, Thomas. “Temporal Vertigo: An Interview with John Akomfrah.” Senses of Cinema, 11 July 2016, sensesofcinema.com/2016/feature-articles/john-akomfrah-interview/.

Childs, Martin. “General Marcel Bigeard.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 30 June 2010, www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/general-marcel-bigeard-soldier-who-served-in-three-conflicts-and-became-an-expert-on-counter-2015150.html.

Dillon, Brian. Essayism. Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017.

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “John Akomfrah: 'I Haven't Destroyed This Country. There's No Reason Other Immigrants Would'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 Jan. 2016, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jan/07/john-akomfrah-vertical-sea-arnolfini-bristol-lisson-gallery-london-migration.

Eshun, Kodwo, and Anjalika Sagar. The Ghosts of Songs: the Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective, 1982-1998. Liverpool University Press, 2007.

Morton, Timothy. “Adbusters.” Adbusters, Nov. & Dec. 2017.

Evans, Brad. “Histories of Violence: Landscapes of Violence.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 5 June 2017, http://lareviewofbooks.org/article/histories-of-violence-landscapes-of-violence/.

Fisher, Mark. “The Land Still Lies: Handsworth Songs and the English Riots.” Sight & Sound, British Film Institute, 1 Apr. 2015, www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/comment/land-still-lies-handsworth-songs-and-english-riots.

Muñoz, Bárbara Rodríguez. “John Akomfrah: Hauntologies.” Carroll / Fletcher, 2012, www.carrollfletcher.com/usr/library/documents/main/hauntologies_publication.pdf.

O'Hagan, Sean. “John Akomfrah: 'Progress Can Cause Profound Suffering'.” The Observer, Guardian News and Media, 1 Oct. 2017, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/oct/01/john-akomfrah-purple-climate-change.

Sandhu, Sukhdev. “John Akomfrah: Migration and Memory.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 20 Jan. 2012, www.theguardian.com/film/2012/jan/20/john-akomfrah-migration-memory.

Sandhu, Sukhdev. London Calling: How Black and Asian Writers Imagined a City. Harper Perennial, 2004.

Scovell, Adam. “A Musicological Study of Ken Russell's Composer Films – Part 2 (Monitor and Bartok).” Celluloid Wicker Man, 12 Oct. 2015, http://celluloidwickerman.com/2014/07/21/a-musicological-study-of-ken-russells-composer-films-part-2-monitor-and-bartok/.

“Exhibition Guide: John Akomfrah: Vertigo Sea.” Talbot Rice Gallery, 2017, www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/jaguide.pdf.

“John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea : Artist Talk.” Performance by John Akomfrah, et al., Talbot Rice Gallery, Nov. 2017, https://vimeo.com/239818481.

Tracy, Andrew, and Nina Power. “Deep Focus: The Essay FIlm.” Sight & Sound, Aug. 2013, www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/deep-focus/essay-film.

Weiss, Haley. “John Akomfrah and the Image as Intervention.” Interview Magazine, Jason Nikic, 29 June 2016, www.interviewmagazine.com/film/john-akomfrah.