A cinephile’s paradise, from Lisbon to Mozambique: Erika Sella revels in Miguel Gomes’ sublime story of love, memory and loss.

Image courtesy of New Wave Films.

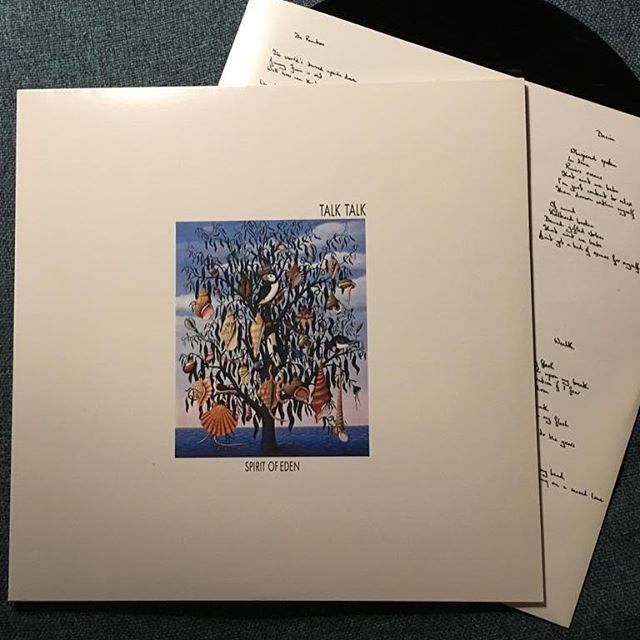

Well-received at last year's Berlin Film Festival and critically acclaimed upon its recent theatrical release, 'Tabu' is Miguel Gomes' third full-length feature, after The Face You Deserve (2004) and Our Beloved Month of August (2008).

Visually stunning, the film benefits from some bold aesthetic choices: Gomes makes effective use of both 35mm and 16mm film stocks and infuses his work with playful references to both European and Classic Hollywood silent cinema. Tabu is formally divided into two parts: the first, A Lost Paradise is set in modern-day Lisbon, whilst the second (Paradise) takes us all the way back to 1960s colonial Africa via a flashback of sorts.

The film's thematic preoccupations are evident from the moving yet

vaguely absurd prologue. It tells the story of a 19th century explorer who is

haunted by the memory of his deceased wife. Her reminder "You cannot

escape your heart" prompts his suicide - he drowns and gets eaten by a

crocodile who later adopts the melancholic posture of its victim, becoming a

sort of emblem of lost love and anguished memories.

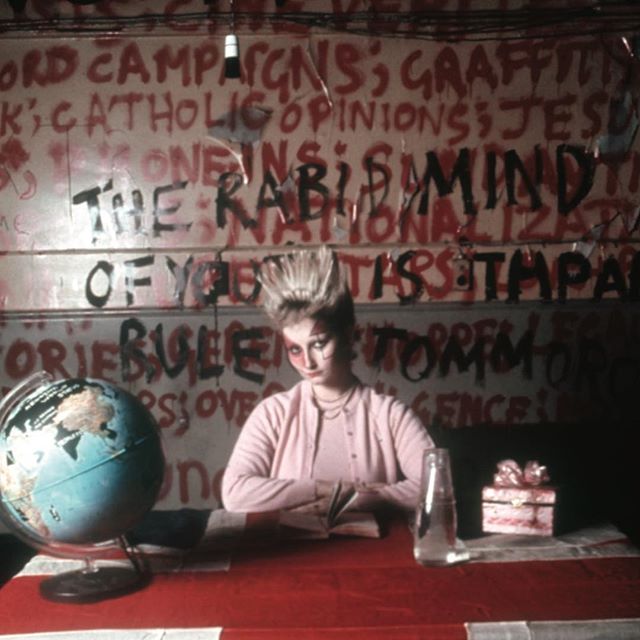

When we are introduced to Aurora, the elderly chronic gambler who is constantly accusing her stoic maid Santa of witchery, we realise that a similar tragic loss might have marked her life: clearly abandoned by her loved ones, she claims to have blood on her hands from misdeeds she committed in her youth. She is often visited by her compassionate neighbour Pilar, who shows deep concern for her, but may also have a few issues of her own. She is unable to respond to her painter friend's clumsy romantic advances, yet she still experiences a strong sense of loneliness and longing for passion and excitement (we see her cry in the cinema to the sound of a Portuguese version of Be My Baby).

Image courtesy of New Wave Films.

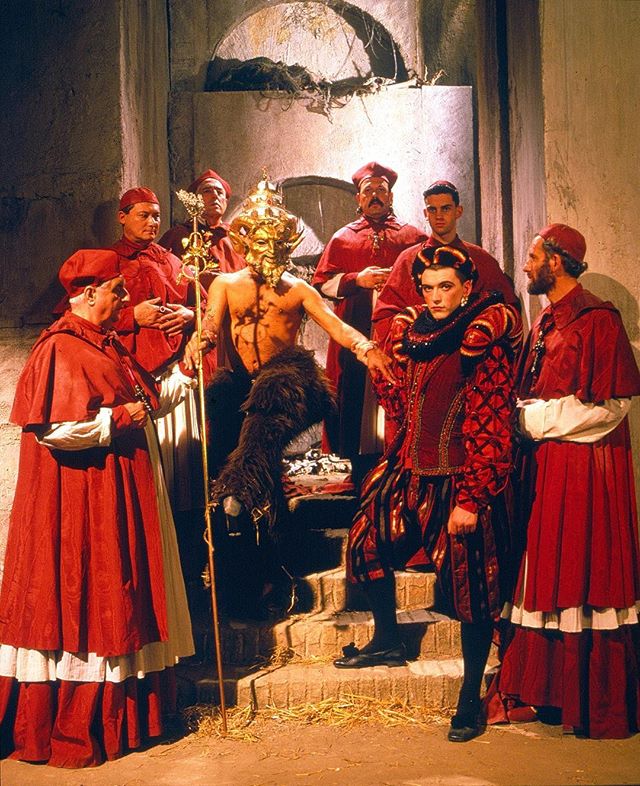

Aurora's death prompts the visit of her former lover Gianluca Ventura - his recollections of their youth allow Tabu to really get into the swing of things. Set in 1960s Mozambique, Paradise is a hazy and evocative tale drenched in cinematic nostalgia. Gianluca's narration shapes the events as the on-film dialogue is inaudible: it is a quasi-silent section (most diegetic sounds are retained) that makes full use of the grainy, dream-like B&W 16mm film stock and Academy Ratio. Gomes even references F.W Murnau's and Robert Flaherty's 1931 film Tabu: A Saga of The South Seas through the diptych structure and tale of star-crossed lovers. Cinephiles should also be able to detect allusions to Sunrise (1927) and early Hollywood adventure films, such as Trader Horn (1934) and the Tarzan series. And whilst she finds cinema incredibly boring, Aurora works as a technical advised on a big-budget flop called It Will Never Snow Again Over Kilimanjaro. With the use of now extinguished cinematic forms, it's almost like the film itself is haunted by its own past.

Yet Tabu is not a mere throwback to the silent era. The film's underlying humour is evident in the many elements that disrupt the overall 'vintage' look of the film: this applies to some of the film techniques used (slow motion, tracking shots) and to the 1960s Phil Spector-inspired soundtrack. At one point, Gianluca's band are playing at a pool party. They suddenly break into The Ramones' Baby I Love You (a song recorded in 1980) - a deliciously surreal sequence that borders on the post-modern, questioning the 'fixed' way we have of viewing the past. We even see children wearing football tops bearing the logos of mobile phone brands.

Gomes seems to be constantly reminding us that what we are watching is not a matter-of-fact story as told by an authoritative and omniscient narrator (as it happens with films like Amelie, The Royal Tenembaums or Jules et Jim). What we have is someone's very personal memory - it could be argued that with the process of his narration, Ventura almost re-invents Aurora. Indeed, in one of her love letters to him, she states: 'The image you hold of me hardly resembles reality'.

In a way, Tabu

seems to be a celebration of story-telling: Gomes has remarked that 'we all

have a need for stories and romance'. This is certainly true of Pilar, a woman

so clearly fascinated with Aurora's story, but also of Santa, who finds

strength and self-realisation in the pages of Robinson Crusoe. We could even consider the Paradise section as a gift, not only to the audience, but also to

the characters we are introduced to in the first half of the

film.

Thematic complexities aside, Tabu

's strength lies in a very personal yet universal story of love, loss,

friendship and betrayal. It is a film of nuances, and the moods and

atmospheres it conveys are just as important as any narrative: in this sense

Gomes approaches cinema at its purest form, and that can only ever be a good

thing.

‘Tabu’ will be released on DVD and Blu-Ray on 14 January 2013 by New Wave Films.