Opening

track Prism is well named, light cuts

through clouds of aural murk, then transforms into the piercing, chaotic,

trebly piano arpeggi of Virginal I

which glisten, flicker, dim in the dark. Already the melodies (if that’s the

right word) reflect that of Ravedeath,

1972, but it’s not about the melodies, it’s a record that continues

Hecker’s exploration of texture. He reflects a kind of abstract expressionism,

Rothko blown up to an even greater, gothic scale, strip-lit and metamorphosing

before your eyes. Such verbiage may invoke a digital version of, say, Morton

Feldman but Virgins is no For Philip Guston, it’s not

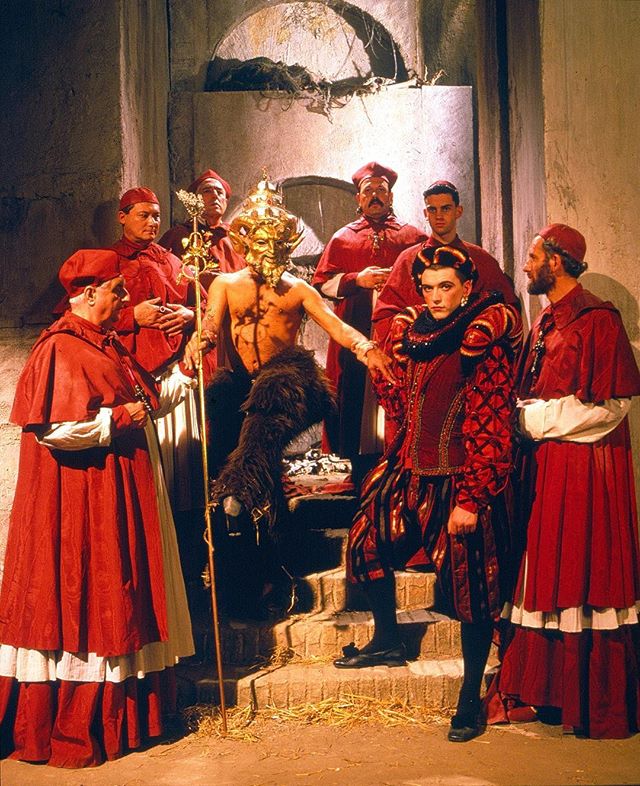

self-important and it billows along at a pace, Lynch meets Argento. There are

traces of the latter’s favoured composers Goblin, as well as the former’s

forays into in sound design and composition (most particularly the industrial

soundscape of Eraserhead); Live Room is the more bombastic moments

of Suspiria both inflated and muted,

twisted, creepy, with creaking, straining, diegetic sound thrown in too – you’re

in the horror film with the score deafening

you as you desperately scramble away from your assailant.

If that all

sounds over-the-top then the empurpled prose is at fault, not the music which -

while demanding to be played at considerable volume - is never anything other

than well measured. For all its BIG moments, Virgins also has plenty of quieter ones too, as with Live Room Out,

the ghostly, more minimal sibling of its similarly named predecessor, or Black Refraction’s repeating piano

motifs, fragments of a depressed Satie heard through a stretched tape loop at a

séance, clattering medium’s table and all. The use of ‘real’ or ‘room’ (read

non-instrumental) sound in some ways disrupts the engagement of the listener,

but it also draws the listener further in – what noise is in the room or

environment that you occupy, and what is on the record?

This is one

of the more readily identifiable markers of what makes Hecker such a peerless

composer-producer; while the use of digital instruments and manipulation is

overt, its collision with the acoustic, the analogue and the ‘real’ often

leaves one unclear as to where one element ends and the other finishes; this

miasma never feels forced (although it does sometimes feel like there are

elements being pushed together with great force), it is always purposeful.

Virgins may not be a work that seems terribly subtle

on first approach, but it is in fact nuanced, intriguing, entrancing,

disquieting. Just as Francis Bacon’s art sought to “Return the onlooker to life

more violently”, Virgins finds Hecker

approaching a return of the listener to life more spectrally (in both sense of

the word). There is a deep, dark undertow to this record, but light pierces the

void in continually surprising ways, in a kind of inverted chiaroscuro; Hecker

ably demonstrates that light is essential to render the darkness all the more appealing.

Tim Hecker’s ‘Virgins’

available worldwide on Kranky (except for Canada where it is available on Paper

Bag Records).

Andrew R. Hill