Derek Jarman’s oeuvre can be a hard sell, but it shouldn't be. It’s slippery, inconsistent, frustrating, sometimes hopelessly dated, opaque, silly and occasionally outright tedious. It is also beautiful, funny, tender, intelligent, ahead of its time and absolutely fascinating. Sometime it’s all of these things at once, taken both microcosmically and as a whole. Lavishly presented by the BFI, Jarman Volume 1: 1976-1986 covers his earliest filmed work through to Caravaggio, along with a plethora of supplementary material including short films and exclusive interviews with many of his collaborators, all presented on Blu-ray for the first time.

The famously queer filmmaker’s early life was marked by an absolute denial of his sexual self - following a humiliating and brutal Catholic education, he buried it under art and education until the age of twenty-two. Rupture eventually came, and proudly so – what would follow was redolent of Cocteau: “In France this vice does not lead me to prison because of the way Cambacérès lived and the longevity of the Code Napoléon. But I will not agree to be tolerated. This damages my love of love and of liberty.” Loudly realised with his first feature film, 1976’s Sebastiane (co-credited, much to Jarman’s chagrin, with Paul Humfress) was the first explicitly homoerotic film to be screened in the UK. This affords it a certain importance, undeniably, but it is often quite a boring watch (on the surface, at least, to a heterosexual male viewer like this writer, who can’t get too much out of the frequent and extremely long shots of toned, tanned men bathing in the nude – this is not a criticism per se, the film was made with a homoerotic intention and, so, a heterosexual male is not the primary audience).

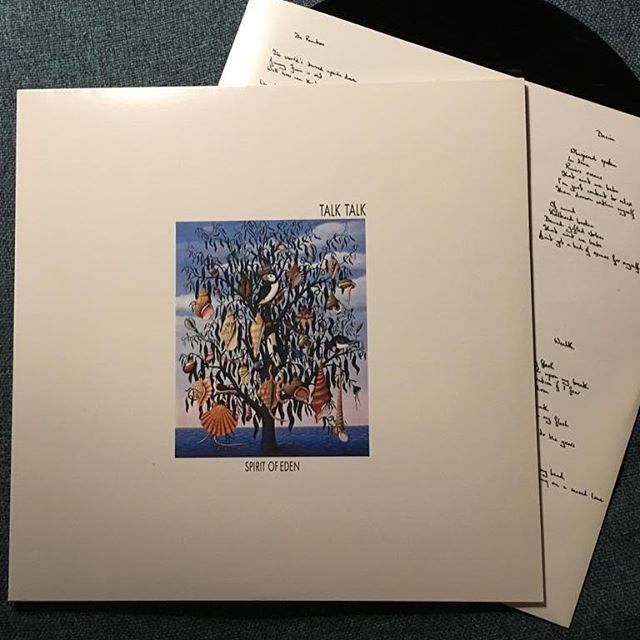

Sebastiane. Image courtesy of the BFI.

The film becomes more interesting when one considers Jarman’s hostility to the film’s subject, the Third Century martyr, Saint Sebastian, who he once described as “the doolaly Christian who refused a good fuck, gets the arrow he deserved”, asking “Can one feel sorry for this Latin closet case?” It marks the film as a tentative setting out of his stall – unashamedly gay and furious at the abuse, violence and repression he had been subject to as a result of his sexuality. St Sebastian is his former self, a person he could never be again.

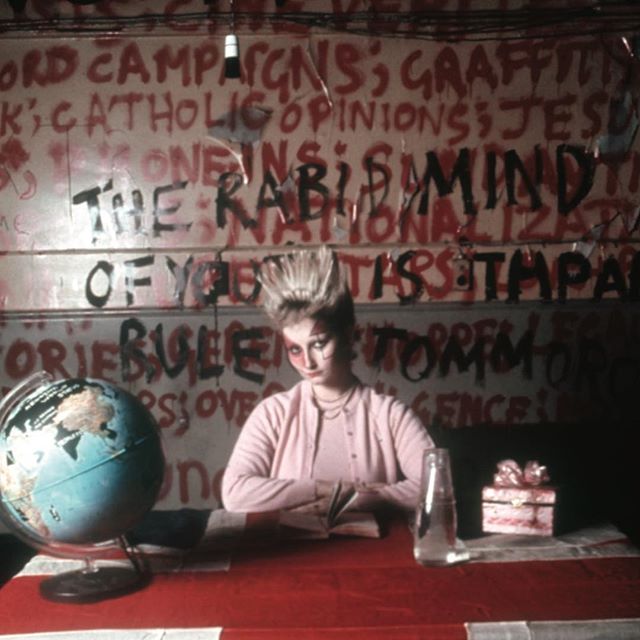

Rage courses through these films, a rage that Jarman would say was unleashed by the punk movement – this is most obviously realized by 1978’s Jubilee, as fervently anti-establishment as it is critical of the punk movement itself. Taking place in a dystopian near-future, the punk’s have won but not much seems to have changed but for a further degeneration of societal integration. Oh, and Queen Elizabeth I has travelled through time with the alchemist John Dee and the angel Ariel, to see what it’s all about. Jenny Runacre plays both QEI and one of the punks, Bod, and this dual role, along with QEI’s placid, thoroughly regal, benignly anachronistic presence is as good an emblem as any to the conflict(s) within the film: a love of an old, genteel idea of England set against an admiration for the would-be anarchy of punk and anger at an oppressive/regressive establishment. The punks in the film, led by punk icon Jordan’s superlative turn as Amyl Nitrate and including Adam Ant as Kid and Toyah Wilcox as Mad, generally doss about causing trouble – they test the audience’s patience but we’re on their side, at least eventually, especially following particularly brutal behaviour on the part of the police (you could easily cheer when two policemen are killed, such is their characterisation, presaging the wholly deserved portrayal of the police as Thatcher’s personal army before she’d even made it to No 10).

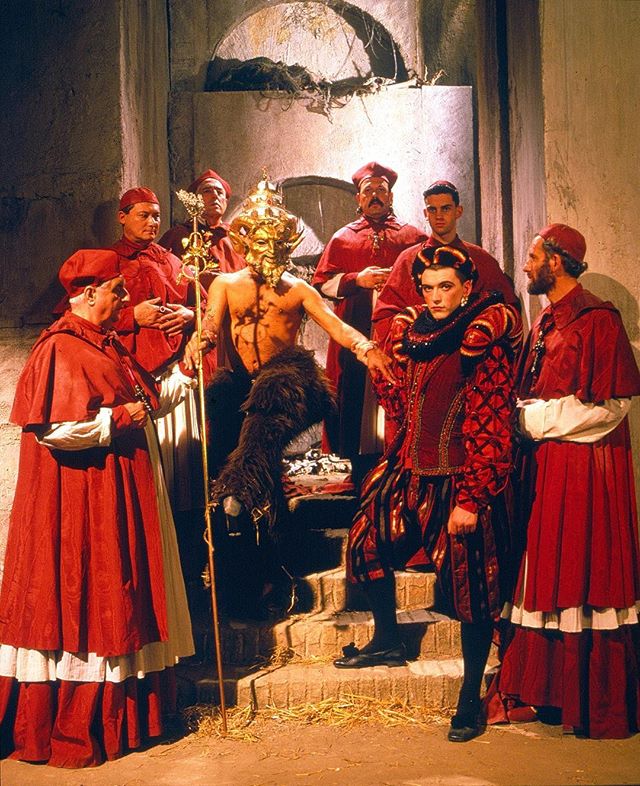

Jubilee. Image courtesy of the BFI.

This sympathy withers at the film's close. Head of the world’s media, Cardinal Borgia Ginz (played with outrageously camp relish by Jack Birkett AKA Orlando), courts the punks throughout the film and eventually wins them over into the ultimate sin – selling out. Ginz is an emblem of the pernicious rise of commercialisation that Jarman hated, and the punks are victims just like anyone else, albeit ones we are very disappointed with (would you like some butter with your car insurance?); that he is a cardinal (‘cardinal’) surely no coincidence either. But as Ariel says, “Consider the world’s diversity and worship it. By denying its multiplicity you deny your own true nature. Equality prevails not for the gods’ sake, but for man’s. Men are weak and cannot endure their manifold nature.”

Ariel appears, of course, in Jarman’s next film, The Tempest, an oneiric cut up of Shakespeare’s text that convincingly conveys the sensation of being locked away while a storm or blizzard rages outside. Heathcote Williams’ Prospero quietly menaces, Toyah Wilcox’s Miranda drifts dreamily and Jack Birkett just about steals the show as the frequently fulminating Caliban, eating raw eggs and spitting out lines in his typically campy manner (Christopher Biggins turns up at one point too…). While the original play is arguably dismembered somewhat in its service, the film is among the more successful Shakespeare adaptations you could hope to see, heavy on (Cocteau-esque) atmosphere and fore-fronting the poetry of the text.

Indeed, perhaps Shakespeare needed Jarman as an editor – Prospero’s famous speech from Act 4, Scene 1 of the original now appears as a wholly fitting, climactic knockout:

“…We are such stuff

As dreams are made of; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

The whole film builds toward this moment, a successful reclaiming of Shakespeare from a British establishment that Jarman would come to vociferously despise over the following decade or so, an antipathy that progressed in parallel with Thatcher’s efforts to hollow out the country.

The Angelic Conversation. Image courtesy of the BFI.

Shakespeare is central too to Jarman’s The Angelic Conversation (1985) but it is in some ways as unsuccessful as The Tempest is successful, though this impression may simply be a matter of format - it is simply too ponderous to be properly enjoyed in a home cinema context, and is ill-served by some particularly period video techniques. Two men move through gloomy landscapes in a serious of slow-motion Christian/AIDS allegories while Judi Dench periodically intones Shakespeare’s sonnets. There is no doubt that the film was very personal for Jarman and some of the imagery is very striking, but the testudineous pacing makes its seventy-seven minutes an endurance test, at least in your sitting room - a gallery installation feels like a more appropriate setting (the same could be said of Disc One’s In the Shadow of the Sun), or indeed the cinema.

Not so Caravaggio. Opening with the titular figure dying of a fever, the film skips back and forward through the artist’s life, reality twisted by the way that memory afflicts itself. Anachronisms abound (a gold calculator, a linen suit, dinner jackets) in a particularly dank and grimy Rome. There are visual nods to many paintings, not just Caravaggio’s, Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat, for one – Jarman the art historian, perhaps. The attention to Caravaggio’s work is not slavish in its reproduction of his paintings (impressive though many of them are), nor are the settings from which he paints quite what we’d expect – Jarman the artist shows us the alchemical leaps that are made from reality to the canvas, the artist as conduit. Nigel Terry’s turn as the brooding artist is impressive and subtler than it might’ve been, given the biography involved and Jarman certainly affords Caravaggio a narrative that both acknowledges and transcends the mad-artist-turned-madder-murderer story to which we are accustomed. It may be Jarman’s most accessible film, but it also seems a perfect fit for Jarman as we know him: an outsider and an insider, a transgressive and a conservative (self-described, presumably with a minuscule ‘c’).

This box set provides an intricate and intriguing detailing of an artist’s development from punky independent to established transgressor. It is not always easy to watch these films, but they are always, intelligent, and more complex than facile viewing sometimes indicates.

Caravaggio. Image courtesy of the BFI.

Gina Birch of The Raincoats wrote the following of Jarman’s work:

“We now think of film and TV as the way of capturing reality. We are programmed to think of it as ‘real’. But is it more real than the time before we discovered perspective, when there was an honest selectivity about what was considered most important/ Derek’s films introduce us to a different kind of reality, a world of the interior mind – feelings, thoughts and dreams – that impinges on our view of the exterior world.”

One could go further – perhaps his work suggests also that the exterior world impinges on the interior; the subjectivity of our existences blurs the boundary between both states - the interior world may be more important than the exterior, but not solipsistically so. Our own feeling, thoughts and dreams can only ever really be our own, but they blur the boundaries between reality and each one of our inner selves. Derek Jarman’s very particular, peculiar cinema bears that out in a very particular, peculiar and captivating way.

Jarman Volume 1: 1976-1986 is out now on limited edition Blu-ray on BFI. A second volume will be released later in 2018.

Andrew R. Hill