The original line-up of Jazzateers met by coincidence seeing David Bowie give his legendary performance as The Elephant Man in New York, despite all coming from the (then slightly Wilder) West of the Central Belt of Scotland. Ah yes, this was a (nearly) Postcard band after all. Tall tales aside, the band had numerous singers through its existence from 1980 to 1986, Don’t Let Your Son Grow Up To Be A Cowboy documenting their time fronted by Alison Gourlay, and her replacements, the sisters Rutkowski (later of This Mortal Coil); Paul Quinn was also in the Rutkowski-modified line-up but does not appear here and songwriter and guitarist Ian Burgoyne steps in to sing a couple of numbers too. One would expect a lack of cohesiveness as a result (this is a compilation, after all) but it doesn’t quite work out that way – there’s a definite split between the two bands, but it’s no less enjoyable as a result.

Read MoreEdwyn Collins

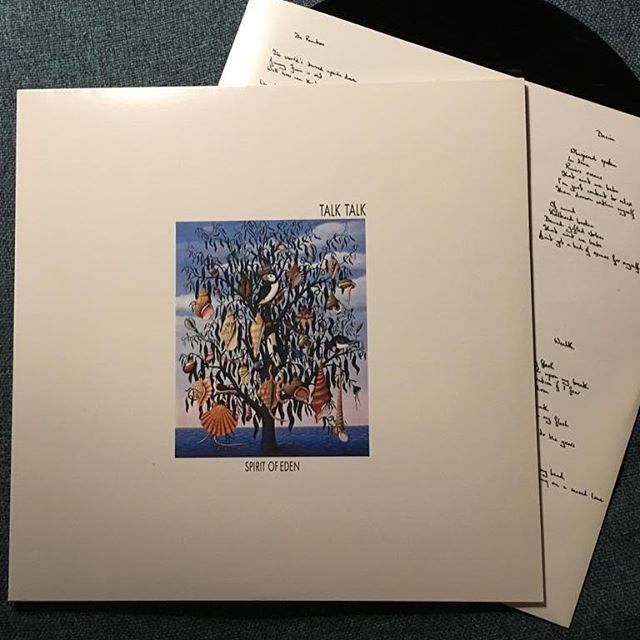

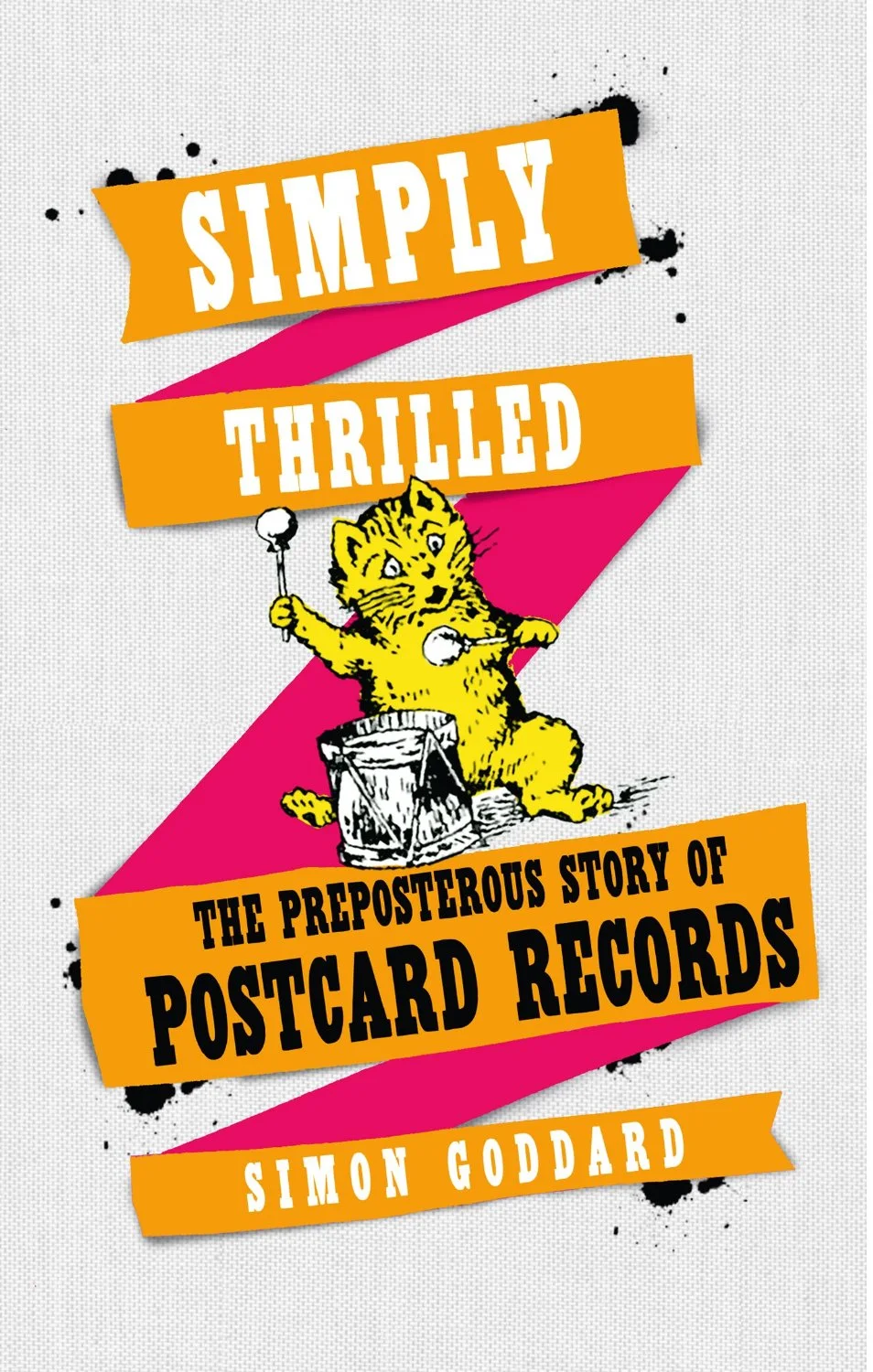

'Simply Thrilled: The Preposterous Story of Postcard Records' - Simon Goddard

Simon Goddard’s whimsical account of Postcard is prefaced by Maxwell Scott’s oft paraphrased “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” It’s a quote that is key to understanding and enjoying the book. It does not ‘set the record straight’, it is not a reference manual of endless gigographies and timelines – if that’s what you’re after, that book is yet to be written. Simply Thrilled: The Preposterous Story of Postcard Records is not a hagiography per se – the presence of myriad acts of self-defeat (and, every now and then, incompetence) and acid-tongued put-downs run rather contrary to most accounts of sainthood – but it does indulge the mythmaking, as well as further romanticising that which has already been significantly romanticised. It’s an engaging read, for all that the line between fact and fiction is often knowingly blurred (quite where is far from apparent much of the time, although Goddard does occasionally illuminate the reader with footnotes on particularly contentious matters).

Following a prologue explaining the life Victorian cat illustrator and inadvertent Postcard logo designer Louis Wain, Goddard introduces us to the Mitty-ish, Saltcoats-dwelling teenage Alan Horne, perennially setback by “fate’s cruel ministers” (a fate used recurrently to great comic effect); most readers will know how integral he is to the Postcard story – in some ways, Goddard renders it all the more incredible that he could be. From there, Goddard recounts his absurd tale of the (still) influential phenomenon that was Postcard Records (slogan ‘The Sound of Young Scotland’): short-lived, a haphazard lurch from genius to disaster and back again, full of youthful bravado and naivety, all the while producing some of the most jaw-droppingly vivacious music ever recorded (although none of it could ever measure up to Pale Blue Eyes for Horne, of course). Horne, Edwyn Collins and co. believed they could take the charts and were outward-looking, without ever losing their very Scottish sense of humour (and periodic self-destruction). Orange Juice were from Bearsden, Josef K Edinburgh, Aztec Camera East Kilbride – all pretty close to each other – but the Go-Betweens were from Brisbane; nonetheless, they weren’t afraid to play with a particular image of Scotland as well (see the label 7” sleeves from 1981).

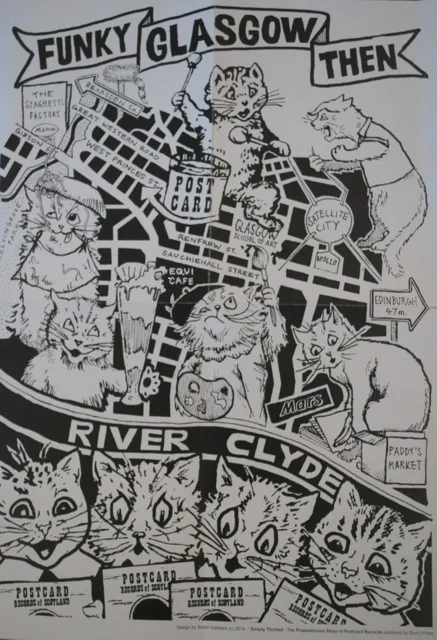

'Funky Glasgow Then' map - a Record Store Day exclusive

The book presents the Postcard story as just that: a tale, a fable, a ripping yarn. Its is a compelling narrative and often laugh-out-loud funny; the overly florid language can be a tad overpowering, even a bit grating (particularly at first), but the eccentric subjects lend themselves to it (how many debut singles – how many songs, for that matter - have used the word ‘consequently’?). There is also the risk of the humour overwhelming an inspiring story and rendering its protagonists parochial bumpkins – it narrowly avoids doing so by the obvious affection Goddard has for his subjects (as well as the fact that these stories have come from the participants themselves). There is an obsessive fanboy in this writer that is perhaps a bit disappointed by a lack of endless hard facts and figures, trivial minutiae, but that same anorak-bearing, social incompetent was also enthralled to read the myth recorded in black-and-white. Finally. Postcard (the records, the idea of it) is held close to the hearts of many – Goddard’s book will certainly not detract from this, he may well serve to enhance it. There’s certainly a lot more to be said about the journeys that the talents of Postcard took, but this book gets things off to a flying start. Ye Gods.

Andrew R. Hill

'30 Odd Years' - Vic Godard

BBC 6 Music DJ (and former member of The Fall) Marc Riley refers to Vic Godard as ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’ and after listening to 30 Odd Years quite a few times now, it’s hard to disagree (as far as songwriters go, anyway). His influence in the late-‘70s was significant and it resonates to this day. Godard (né Napper) took the emancipatory energy of punk and applied his inchoate yet sophisticated songwriting nous to it, filtering a variety of genres through both over the decades. From 1978’s Don’t Split It through to a 2012 rendition of 1992’s Johnny Thunders with Davey Henderson’s marvellous Sexual Objects, there’s no ‘Joey-punk’ knuckle-dragging and not a hint of flab.

The first disc is the more straightforward of the two, although it may raise the eyebrows of the hitherto uninitiated: it starts off punk (albeit with a smart, cutting, ‘60s garage edge), develops into Velvets-tinged pop, swings into full ‘Cole Porter’ mode in the middle, briefly turns off into the best Bond themes you’ve never heard (Spring is Grey and Stayin’ Outta View (Instrumental)) and ends with muscular Edwyn Collins-produced Northern Soul. All this could surprise even the seasoned fan with a full pre-existing familiarity with the individual songs.

The second disc initially follows naturally enough with We’ll Keep Our Chains from Godard’s second Collins-produced Long Term Side-Effect – melodic, tough, a bit off kilter and underpinned with that trademark Northern Soul swing. But then the generic twist-turns begin to emerge in ever more awe-inspiringly unexpected ways. First there are two infectious gospel songs from LTS-E and then we’re into turn-of-the-century urban with The Writer’s Slumped, which has more than a hint of Missy Elliott’s Get Yr Freak On about it (which came first, one wonders?). There’s even Godard classics such as Ambition with a distinct good-ole-fashioned-hoe-down bent, blackly funny music hall in the form of Blackpool (the theme to an ill-fated theatre collaboration with Irvine Welsh) and the jaunty, accordion-led, Brechtian number The Wedding Song. The most incredible thing about all of these diversions is how natural it all sounds – partly a testament to picking collaborators of the finest calibre but primarily due to being possessed of a songwriting talent, an authorial voice, so definite and distinct as to frequently leave one breathless.

The last song proper is the aforementioned live rendition of Johnny Thunders with The Sexual Objects. Recorded at Stereo in Glasgow in December 2012, it was a performance that was a part of a series of events dubbed VIC.ism, the weekend-long Glasgow leg of which celebrated Godard’s influences, influence and his special connection to the local music scene (his connection to Scotland is emphasised further by excerpts of the late Edinburgh poet Paul Reekie discussing Godard and Subway Sect on the short intro and outro tracks). 30 Odd Years reinforces the extent to which Godard’s back catalogue and fulsome talents deserve to be celebrated and emphatically so. Even the Godard/Sect aficionado is likely to uncover a fresh understanding, not least because of the wealth of alternative versions, radio sessions and live recordings on offer. The promise of a further Edwyn Collins-produced record, 1979 Now, later in the year is very exciting indeed, and if ever a 40 Odd Years appears, one could be confident it would be every bit as essential a listen as its predecessor.

'30 Odd Years' is available now on Gnu Inc Records on CD and download.

Andrew R. Hill