A documentary that is prefaced with a quote from The Book of Job rarely creates anticipation for a light-hearted romp. Leviathan begins with such a quote in white text on black, an extract from chapter 41 regarding the titular beast. We fade to black; deep metallic groaning as water laps in surround sound, light leaks in, red and then an image forms: waves, the deck of the boat, a fisherman’s gloved hands – our hands in fact, as the camera’s eye is the fisherman’s. We’re hauling in a catch, an enormous net, the trawler leaning toward the sea. We could go in those waves at any moment and then, apparently, we do. Have we gone overboard? No – this camera moves about as it pleases, possessing fishermen, swimming in the wake of debris, climbing nets, writhing among gawp-mouthed fish, defying gravity. The camera is our narrator. From that slow fade in, we plunge into a semi-psychedelic miasma of images and sounds, edited into a practically seamless hallucination. This is no ordinary documentary.

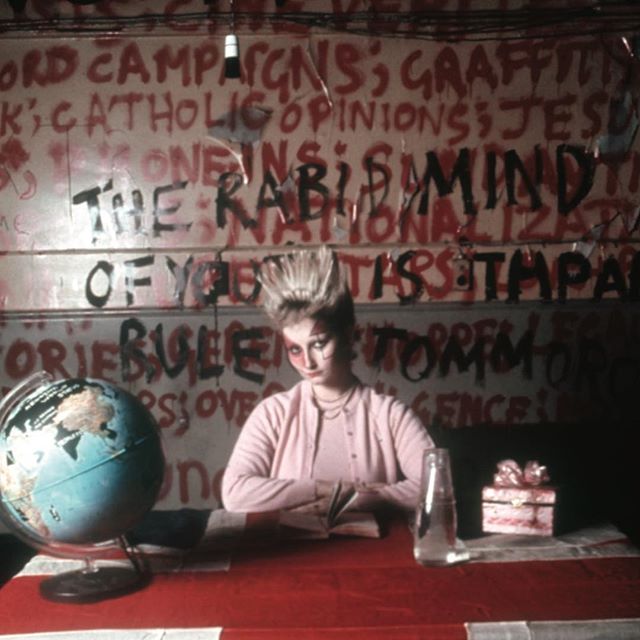

Image courtesy of Cinema Guild.

In acid-droppers’ parlance, this is a bad trip. The fishermen live on a knife edge, everything is poised on the brink of destruction at all times, it’s dark and it’s wet and it’s choppy as hell. The camera eye, our eye, is unflinching: fish writhe and suffocate, and are beheaded and gutted with ruthless efficiency by the fishermen – in this initial sequence – mostly faceless, sou’westered automatons. The physicality of their job combined with the harshness of their environment makes it hard to believe they’re human sometimes. In one grimly hypnotic sequence, two fishermen remove the fins from stingrays, hooking them through the eye, hacking off the fins and then throwing the three dismembered pieces into buckets - hook, hack, chuck; hook, hack, chuck; hook, hack, chuck – a (presumably) routine process in their day’s work, a routine of metronomic brutality. Later, we see blood and slurry pouring from the side of the boat, back to the sea.

The unsettling horror sequence of the first hour is abruptly interrupted and the film turns round into a more human affair. The fishermen, below deck for the most part, are now human; they still conduct their business in a well-worn manner but we can see their bare faces: physically and emotionally exhausted, damp and hollow eyed. Fish are processed, cranes are operated, incomprehensible New England gutturals exchanged. A hefty, moustachioed man in a vest blankly watches television beneath deck, he doses off and we’re in another frame of consciousness again. A slow-motion, woozy drift, the camera floats in and around the ship, in and out the black water - is this the fisherman’s dream? Is it ours?

To call Leviathan a documentary is in many ways inadequate, a convenience of categorisation. But while it does so in an extraordinary, hypnotic, hypnagogic manner, it actually cuts to the heart of its subject matter by simply showing us, unencumbered by narration or a narrative. In among the viscera of the operations of the boat, we feel the brutality of nature and the brutality of industrialised human consumption. To call Leviathan a horror film is something of an exaggeration too but it might be just as accurate as calling it a documentary: like the best horror films, one is relieved when it’s all over - but the pull of the dark currents, the impulse to plumb those depths again, recurs too.

Andrew R. Hill