Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso (Le mystère Picasso, 1956) is, at least in part, a failure but it is an interesting one. Presented here in a lovingly restored form by the ever-admirable Arrow Academy, it is essential viewing for anyone with an interest in 20th Century art, never mind the singular force of nature it seeks to document.

Clouzot’s stall is set out early in the film, a voice intones:

One would die to know what was on Rimbaud’s mind when he wrote ’The Drunken Boat’, or on Mozart’s when he composed his symphony ‘Jupiter’. We’d love to know what secret process guiding the creator through his perilous adventures.

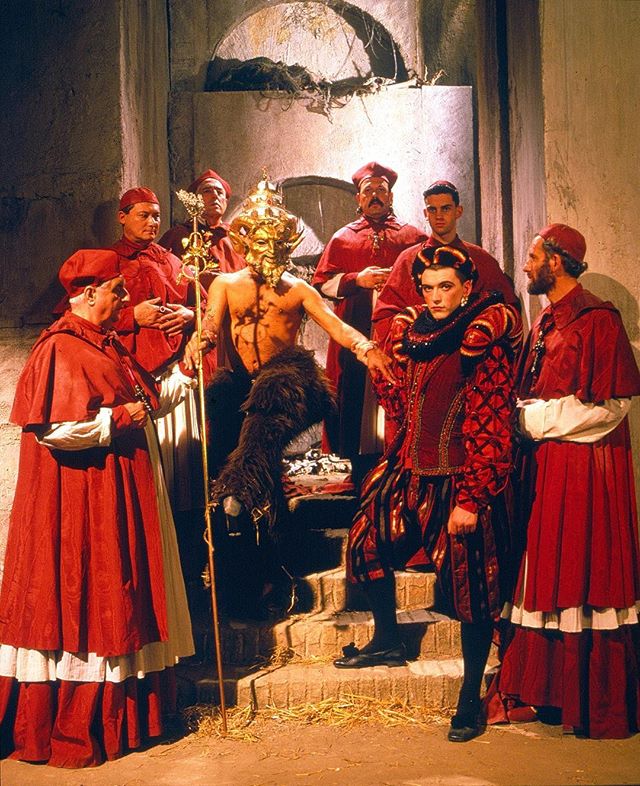

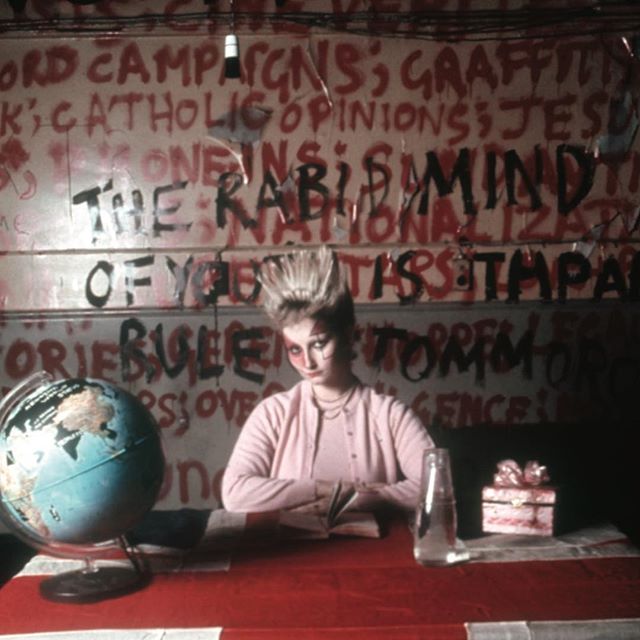

Clouzot doesn’t even get close. Or maybe it’s a red herring? The ‘French Hitchcock’ (a needless Anglophone-centric reduction if ever there was one) has some success in approaching Picasso’s work as an opportunity to build suspense, as was his stock-and-trade. Much of the film consists of specially-prepare canvases reverse-shot, filling the screen while Picasso ‘paints’ using marker pens and special inks on the other side. The ink bleeds through, giving us an unusual sort of animation. This was the first film of Clouzot’s to feature colour, an approach that certainly underlines the jouissance present on/in each canvas. The suspense emerges from the line of questioning most viewers cannot help but ask: where will that line go? What will this form become? What will the background be? When will the next nude or bull or matador or Pierrot turn up?

Shot in nice over three months in 1953, many of the pictures created in the course of the film are recognizable variations of works form the previous few years, typical of Picasso’s ‘late style’ (the body of work created between 1953 and his death in 1973). Of course, there was no one style per se over these twenty years, but it is not too harsh to state that his hitherto constant thrust toward innovation had ebbed by this time. As Cy Twombly once asked in defense of his friend Robert Rauschenberg, “ Do you have any idea how difficult it is to hold the tension over several decades?”

Perhaps the frustrations of this approach could be said to be with Picasso rather than Clouzot. While there is no doubt an appeal to the resultant works Picasso creates, the imposed suspense is rarely satisfied. That said, the suspense is imposed; and maybe that misses the point anyway – in a thriller, the suspense (not the resolution) is the point. Interestingly, this dovetails neatly with Picasso’s own attitude to his art:

For me each painting is a study. I say to myself, I am going one day to finish it, make a finished thing out of it. But as soon as I start to finish it, it becomes another painting and I think again I am going to redo it. Well, it is always something else in the end. If I retouch it, I make a new painting.

The trouble is that often this suspense feels not just imposed but really quite forced, and one cannot help but feel that Clouzot could do with letting the works ‘breathe’ more. The worst element in all this (and in fact the worst thing about the whole film) is Georges Auric’s overwrought, grating score – rather than leading one to be tense through a sense of suspense, one ends up tense through aural aggravation.

Image courtesy of Arrow Films.

To see a Picasso emerge before you is a privilege, no doubt, but the most interesting parts of the film may be where we see the Picasso interacting with Clouzot If it weren’t apparent enough already from the canvases he has created before, Picasso’s enormous sense of playfulness then comes out in contrast to the mostly austere Clouzot - though they do share the odd chuckle. It’s fascinating to see Clouzot excel in his usual stark monochrome yet with a more Brechtian, and less straightforwardly documentary approach. One of these all-too-short sequences leads to more suspenseful drama, Clouzot telling Picasso how long he has left to paint before the film runs out. Interestingly, these segments are score-less and manage to be more suspenseful than those where we directly watch and await the emergence of a ‘complete’ canvas.

If one feels a slight dissatisfaction at the end of the film, it is perhaps the blame of those expectations set up by the opening narration, that somehow we will have a greater insight into Picasso’s work, practice, thoughts, ethos; ultimately, we do not. In some ways this underlines a point made in Walter Benjamin’s essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’:

Magician and surgeon behave like painter and cameraman. The painter, while working, observes a natural distance from the subject; the cameraman, on the other hand, penetrates deep into the subject’s tissue. The images they both come up with are enormously different.

This disconnect may be the source of the sense that something has not quite come off with The Mystery of Picasso. But this is an experiment, and watching both artists working really is a privilege in itself. At the end of The Mystery of Picasso, Picasso and his work remain just that, a mystery – would you really want it any other way?

The Mystery of Picasso is out now on Arrow Academy on blu ray and DVD formats; each features Paul Haesaerts’ 1949 documentary ‘A Visit to Picasso’, ‘La Garoupe’, a 1937 ‘home movie’ by Man Ray, and a short ‘before and after’ feature on the restoration of the film.

Andrew R. Hill

Bibliography

Bazin, André. Bazin at Work: Major Essays & Reviews from the Forties & Fifties. Edited by Alain Piette and Bert Cardullo, Routledge, 1997.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by James Amery. Underwood, Penguin Books, 2008.

Berger, John. The Success and Failure of Picasso. Penguin Books, 1966.

Lewison, Jeremy. “In the Antechamber of Death: Picasso's Later Paintings.” Late Style and Its Discontents Essays in Art, Literature, and Music, edited by Gordon McMullan and Sam Smiles, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Lloyd, Christopher. Henri-Georges Clouzot. Manchester University Press, 2007.