The Filmhouse adds another string to its bow with a foray into distribution. Its debut release, The Stoker, takes a cold hard look at the ashes of post-Soviet Russia. Erika Sella rakes through the soot and the dust.

It’s small wonder that the Filmhouse is a highly regarded institution is Scotland (and the UK): home to the Edinburgh International Film Festival and the world’s oldest film society, the Edinburgh Film Guild, it has recently expanded its remit to film distribution.

At a terribly competitive time, when ‘10 out of 127’ distributors hold ‘the monopoly on the theatrical marketplace’ [1], The Filmhouse have decided to step up to the challenge of picking up and releasing little-known films that quite often get left behind by the traditional commercial model. The choice for their first release is indicative of a relaxed yet highly selective attitude to the industry.

Image courtesy of Filmhouse

Aleksey Balabanov’s The Stoker was never going to be an easy on the eye art-house favourite. The film was made in 2010 and first premiered outside its native Russia at the Rotterdam Film Festival in 2011, before quietly disappearing off the radar. At first glance, it doesn’t appear to be something that was made with an international audience in mind: even though the film deals with universal themes such as isolation and bereavement, its director is relatively unknown outside his native land, and the plot presupposes that its audience will have at least a basic knowledge of Russia’s post-Soviet history, as well as a passing familiarity with the country’s culture.

At its core, The Stoker has got quite literally a burning heart - an oven, something that in Russian folklore represents life, vitality, the family milieu. Balabanov turns this symbol on its head: his protagonist, an ex-military Soviet hero of Yakut extraction (Major Skryabin), works all day and night by a furnace, often turning a blind eye to some local gangsters who use the facilities to incinerate their dead enemies.

Much of the film’s humour stems from the deadpan attitudes that accompany brutal acts - ironically, this is a double -edge sword, as it is also one of the film’s most tragic aspects.

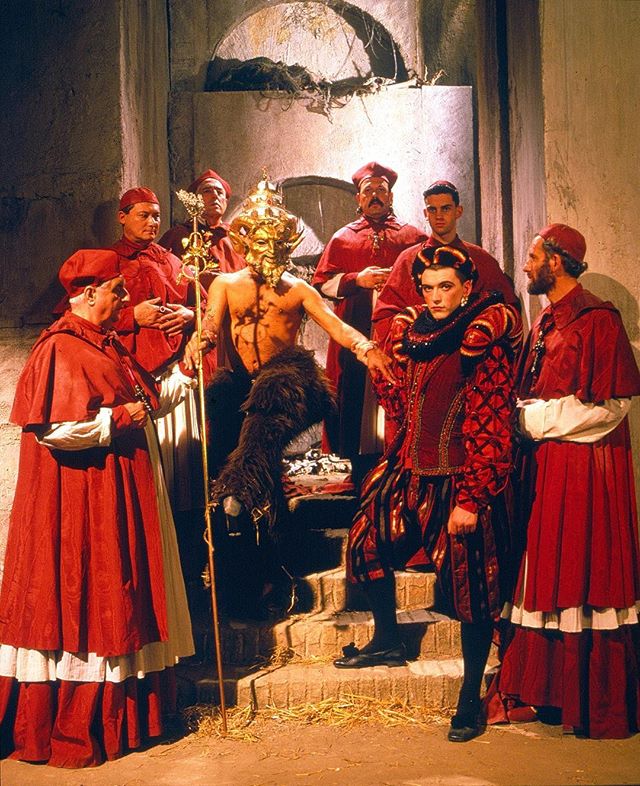

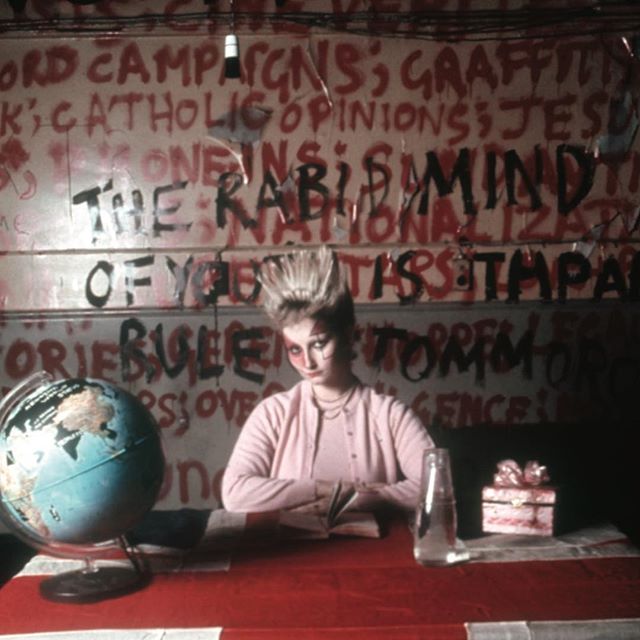

The Stoker is set in the early 1990s, right after the fall of Communism – a time when Russia was essentially run by oligarchs and the Mafia. In a way, it’s no wonder that the film rejects any sort of aesthetic pleasantry: there is something almost lurid about what we see on screen. St Petersburg looks like an anonymous industrial town; flats and houses look inhospitable; men and women (even the objectively attractive ones) seem repulsive; every shot has a grubby, almost ghastly quality to it.

On top of all that, we are also subjected to an extremely repetitive instrumental guitar score that almost drowns out key conversations. While it’s hard not to be irritated by this seemingly incongruous jaunty, folk-infused theme, one has to recognise that its cheapness ends up complementing what we see on screen. Some reviewers called the Balabanov’ s choice of music ‘suicidal’; it’s clearly something that will test an audience’s patience, but it’s also a very brave directorial move.

Actors behave like malfunctioning androids, hardly displaying any emotions at all; the main hitman, ‘Bison’, only utters one sentence throughout the whole film. There is a general sense of malevolence, as relationships and interactions are clearly based on nothing more than reciprocal exploitation. The only exception to this rule is Skryabin: a powerless observer, honest and clearly selfless (he gives all his earnings to his daughter even though this means he has to live by ‘his’ furnace day and night), he puts his head down and carries on in a world that has gone topsy-turvy. At one point, though, things really get too much, even for him.

It’s obvious that even the most basic rules human society is built on are out of the window. Balabanov disposes of most of his characters (the body count is rather high) with little remorse and occasionally in a tragicomic manner. Skryabin’s last lines in the film finally sum up the disarray we have been subjected to: “ This isn’t war. Was is different. There you have us versus them. But here, it is us against us”. Skryabin is referring to his experiences in Afghanistan, but he could easily be talking about post-Communism Russia: gone are the old antagonists of Soviet propaganda, now it’s the time for an inner, and in some ways much more uncomfortable, battle.

For all its (admittedly quite dark) humour, The Stoker is a demanding watch, and it’s easy to see how the film could have disappeared if The Filmhouse hadn’t picked it up. However, its underlying savagery and ugliness feel necessary - the late Balabanov clearly wanted to provoke a reaction in the viewer. And ultimately, this is what elevates The Stoker from a mere gangster film to a striking and thought-provoking commentary of what his country looks like today.

[1] Harriet Warman, ‘Picking Up The Stoker, available at: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/interviews/picking-stoker