It is no remark upon the quality of Different Every Time to say that it is not a ‘very best of’ Robert Wyatt with designs on the stockings of dads up and down the land - mind you, how long is it before John Lewis get the wrong end of the stick and get Ed Sheeran to cover Shipbuilding for their annual Christmas atrocity, as some little Timothy or other attempts to escape his parentally-inflicted mundane bourgeois suburbia with a box for a boat, a desperately tragic triumph of imagination over commerce that only the great middle-class equaliser can rectify? No, rather, this is an unflinching introduction to the breadth of his work from Soft Machine through Matching Mole through almost every fine solo LP to grace his name, and in chronological order at that. How often does a chronologically-ordered compilation of an artist’s work get better as it goes on?

Read MoreDomino Records

'Wig Out At Jagbags' - Stephen Malkmus & The Jicks

Stephen Malkmus & The Jicks’ 2011 album Mirror Traffic was rightly hailed as one of the highlights of the former Pavement singer’s solo career so far. Much was also made of how much it sounded like Pavement, but Malkmus and his backing band have never really drifted all that far from the sound for which he is still best known. The new record, Wig Out At Jagbags, is slighter than Mirror Traffic even if does occasionally feature a broader palette of instrumentation than one was accustomed to hearing from Pavement. One such song is Smoov J, which features a muted horn solo, subtle Hammond and synth strings and trips into outer space on delayed lead lines, before floating gently back to Earth on an acoustic guitar.

Wig Out At Jagbags is sprightly, brief and occasionally throwaway, albeit in the best possible way. Although actually placed closer to the end of the record, Rumble at the Rainbo and Chartjunk feel centrally placed and are rather, well, fluffy - they’re great fun and not much else; the former is particularly amusing as a cutting observation of an ageing punk/’punk’ scene, and the latter features a buoyant horn section ‘70s-toned rolling electric piano.

There’s plenty of melody on this breezy album, but the more cryptic the lyric, the harder it is to connect with it. The wordplay is certainly entertaining (and this kind of lyric writing has been a frequent marker of Malkmus’ songwriting since it first emerged over two decades ago) and reflects an occasional stoned feeling that manifests itself in a kind of absent-minded psychedelia (as opposed to the almost hard rock feel of some earlier Jicks material). There’s no denying there’s a lot of skill in the way these songs have been written and there’s plenty to enjoy, however slippery the (sometimes hyperactive) abstractions get.

'Wig Out At Jagbags' is released today on Domino in the UK and tomorrow on Matador in the US.

Andrew R. Hill

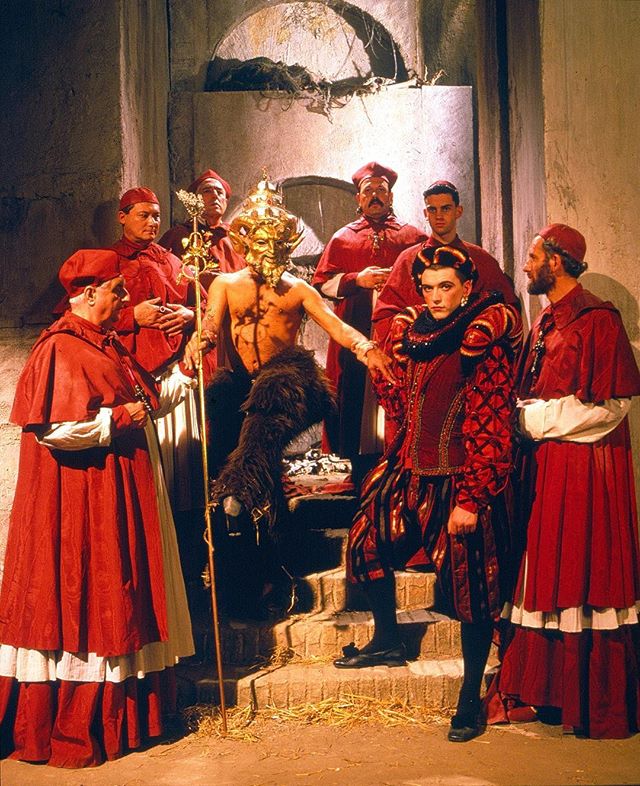

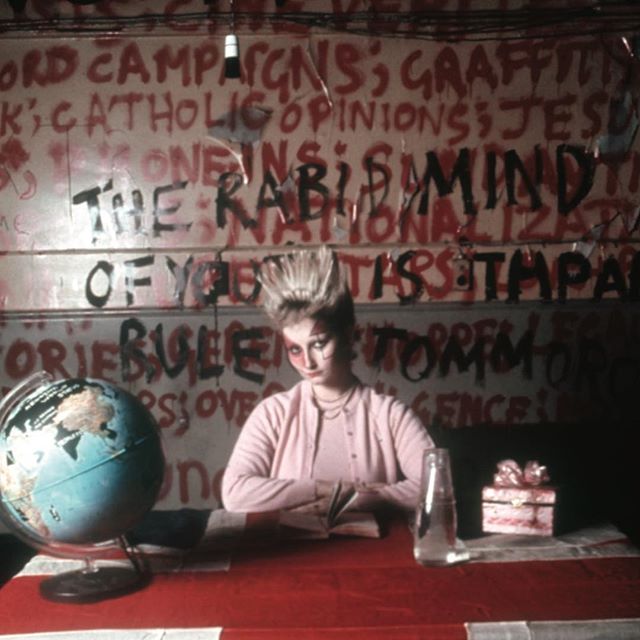

'Loud City Song' - Julia Holter

I began writing this review this as I returned to Edinburgh from London. It’s far from the first time I’ve visited but it was an intense sojourn. I’ve lived in a city all my life (albeit one that feels more like a village sometimes), but even with the seemingly endless noise of the Festival crowds still ringing in my ears, my arrival is met by the roar of the city - a city that is almost too big, too sprawling, to be appropriately accommodated by the term - and it is keenly felt, amplified by the briefness of the encounter. Nothing is quiet. Even late in the night, the city emits a low-level thrum, an electric buzz. Its very scale, in all directions, presents a kind of loudness, whether sonic or visual, actual or imagined. Julia Holter’s Loud City Song does not take London as its titular subject (that honour is bestowed up on Holter’s native Los Angeles as a transposed setting from Paris for Colette’s Gigi) but it does convey the sense of wonder, unreality, confusion and fear that a city can reveal as it unfolds slowly to you for the first time.

Loud City Song opens in an arresting and captivating fashion with World. “Heaven/All the heavens of the world.” Her naked voice is slowly dressed by sparse, solemn instrumentation, strings that creak in heavy groans and sighs in an arrangement that is reminiscent of Scott Walker and solo Mark Hollis – disjointed lyrics can only lend further credence to this comparison (a comparison that can easily be applied to other parts of the record). Holter discusses “All the hats of the world” and her, her hat and the city’s relationships. Then “Everyday I grow older/Every day I grow a bit closer to you”. Closer to who? The song closes thus: “What am I looking for in you?/How can I escape you?” Is it a lover? An assailant? The listener? The city? Death? World is a disquieting and enigmatic beginning to an album that asks more questions than it provides answers to, a quality that makes it all the more enticing - enthralling, even.

World’s questions linger unanswered with a plunge into the immediately hypnotic, intense, blissful Maxim’s I. “I don’t understand” Holter declares, and the music reflects the statement, presenting a scene of cinematic awakening. Impressions of woozy unearthliness recur throughout, and while this has been Holter’s stock-and-trade since her debut album Tragedy, the greater possibilities - and constraints – of recording in a ‘proper’ studio for the first time have galvanised her sense of the otherworldly in a far more compelling way. He previous record Ekstasis was full of ethereal melodies and disembodied lyrics, but it occasionally drifted dangerously close to the New Age insipidity of Enya. Such a flirtation occurs only once on Loud City Song, at its midpoint of (Barbara Lewis cover) Hello Stranger – it’s just a bit too ambient and uncomplicated for its own good, letting swathes of digital reverb do most of the work; that it is a cover speaks volumes of the strength of Holter’s songwriting.

Hello Stranger does provide a necessary break in the album, for all its mildly irritating execution. The album has a dizzying and at times overwhelming build. The third track Horns Surrounding Me pulses insistently then breaks into coruscating organs, delayed vocals and clouds of billowing horns that threaten to engulf both Holter and the listener; the following In The Green Wild builds playfully around lolloping double bass, detuned sound effects and chatty backing vocals before drifting into another place: “There’s a humour in the way they walk/Even the flower walks/But doesn’t look for me/It walks just as it’s grown/It’s laughing so naturally/Ha ha ha ha”. Is this the disoriented city-dweller in the country (as is suggested by the title), or could it be the reverse?

After the wafting ambience of Hello Stranger, Maxim’s II is a curious mix of the acoustic and the synthesized, and brings to mind early solo Brian Eno, as this album occasionally does. Something in its mix of light and shade, pop hooks and out-and-out strangeness, as well as the recurrence of a certain kind of vocal double tracking that echoes Another Green World or Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.

Loud City Song continuously throws curveballs – who expects the almost aggressive Maxim’s II to be followed by the genuinely beautiful piano-and-strings ballad of He’s Running Through My Eyes? Who could expect that to be followed by the playful foray into ‘80s-style MOR pop (albeit a thoroughly subversive and somewhat surreal one, despite the synthetic bossa beat and oh-so-smooth sax solo), This is a True Heart? And then, who could expect the unashamedly cinematic (there’s that word again) finale of City Appearing? On the latter, Mark Hollis once again springs to mind, as does The Walker Brothers’ weirdest moment The Electrician, and this follows a track that sounds a bit like Spandau Ballet or Chris de Burgh if they were female-and-interesting-and-really-good-not-totally-atrocious.

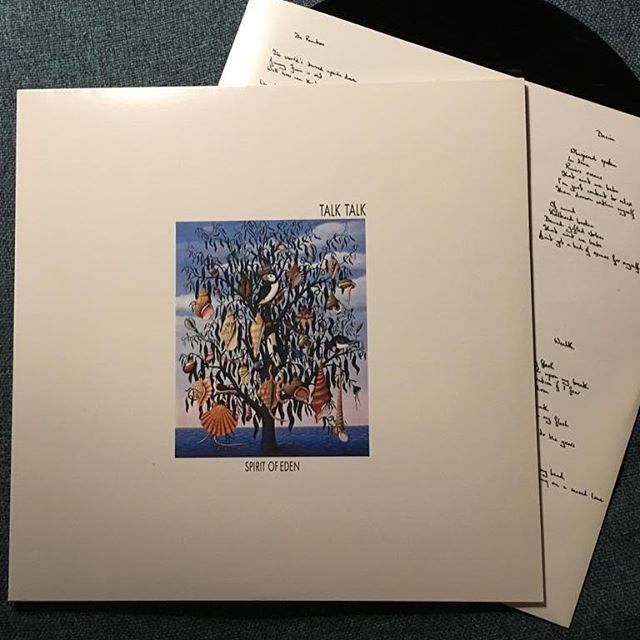

City Appearing opens from a bare voice (like World) and into a slow ecstasy, “Taken by surprise/Taken through the city”. It’s a spaced-out late night taxi drive, a neon sunrise through a rain-spattered window. A cacophony builds, dazzling, spectral - late period Talk Talk on MDMA - then bursts, shimmers…and it’s gone. Like a dream you never want to end, the release into the real word is a shocking one. Dreams tend to slip away over time, become less detailed, degrade; in this sense Loud City Song is far less like a dream and more like a city: one' s experience of it is a continually renewing process of revelation; this record unveils new corners, light and dark, with every visit – disquieting, elusive and seductive.

'Loud City Song' is available on Domino Records now, on CD, LP and download formats.

Andrew R. Hill

'Slow Summits' - The Pastels

The Pastels make a virtue of taking your time with their first album in sixteen (or ten or four) years, Slow Summits, as Andrew R. Hill finds.

It’s taken a while to get there, but it’s been worth the wait; The Pastels’ new record, Slow Summits, is – appropriately – a career high. It’s a record that seemed to threaten to remain inchoate forever, but now, sixteen years after their last album ‘proper’, Illumination, it has manifested as an album that is possessed of vivacity, gentle eccentricity and vibrant melodic brushstrokes, both fine and broad. It expands on a palette that was first exposed with Illumination, greatly developed with 2003’s The Last Great Wilderness soundtrack and further refined with 2009’s fruitful and frequently gorgeous collaboration with Tokyo’s Tenniscoats, Two Sunsets.

Secret Music fades in, reveals itself with an initially delicate arrangement of pattering drums, Gerard Love’s undulating bass and Katrina Mitchell’s voice - somehow both guileless and knowing - before growing into a (somewhat) quiet crescendo as other instruments and voices join in; it’s a perfect opener for an album that ebbs and flows but (slowly and - kind of - quietly) builds - the album title couldn’t be more apt, for innumerable reasons.

There’s a toughness that was missing on Two Sunsets underpinning Night Time Made Us that recurs throughout, and becomes more ferocious each time. It’s grit that’s tops things becoming too pretty, and keeps that certain strain of steeliness that The Pastels have always had present without disrupting the flow of the record (quite the opposite in fact - if anything, it keeps it pushing on). First single, Check My Heart, has a different kind of boldness to it. In primary colours, it’s the sound of summer, of letting go, of almost unbridled joy – almost, because, as with much of this record, even in its most summery moments there are slight melancholic touches, sometimes approaching something of a wistful tone; it’s a matter of light and shade though, and serves to make the sunniest parts all the more coruscating.

The climb continues with Summer Rain, framed with a chord progression that brings to mind Vic Godard and early Orange Juice (and again there’s that underlying toughness); without much warning the song turns around into a spectrally semi-psychedelic coda, something of a hallmark of the latter day sound of the band, and with good reason - they happen to be very good at it. After Image is the halfway break, a pause for reflection that showcases the range of the instrumental touches that pervade throughout the record and provide a kind of sonic canvas, a primer that creates a textural depth and helps the foreground hang together: wordless multi-tracked backing vocals, winding keyboard lines, wheezing melodica, burbling electronic touches and innumerable other instrumental details.

The ascent recommences with the most sumptuous piece in The Pastels’ oeuvre to date, Kicking Leaves melodically and lyrically swoons, and features a string arrangement by fellow Glaswegian Craig Armstrong that manages to be very much to the fore without being cloying or saccharine. It’s the most beautiful passage in a record full of beautiful passages. Wrong Light features an esoteric sing-along moment courtesy of Mr Pastel “Please don’t show/The wrong light/We are the shadows of the night” and a jauntily oscillating flute line, sounding la bit like a lost track from Two Sunsets, albeit crisper than much of that album’s soft-focus psychedelia.

Tom Crossley’s flute is also showcased particularly effectively, as is Alison Mitchell’s trumpet, on the brooding title track. The tone of the instrumental is unexpectedly dark, guitar chords clang against a driving rhythm section. It’s a song that bears a furrowed brow, a determined last push towards the peak. It could easily be the theme to a lost Franco-Tartan film noir, and it’s a bit of a surprise, a chiaroscuro impression that throws the rest of the record into sharp relief, panoramic and breathtaking.

Come to the Dance rounds the album off with a party, all buoyant vocal melodies and strident guitar, the party at the peak, and rightly so - Slow Summits is worth celebrating, as well as a celebration in itself. The Pastels may no longer make quite the polarising racket they emerged with in 1982, but the vivacity rendered in their earlier work remains, and while the music is a little bit subtler, a bit more crafted, that same spirit definitely carries through. This record is affecting and infectious, warm and energetic. Whether the wait has been four, ten or sixteen years by your count, Slow Summits gives the impression that the same interval again would be worth the wait. That doesn’t mean that anyone wants such a long wait for the next one, of course, but there’s clearly something to be said for taking your time.

Slow Summits is out now on CD and LP on Domino Records.