Following the making of his fifteen and a half hour epic documentary The Story of Film: An Odyssey - a project that took six years to shoot – Mark Cousins made the poetic film essay What is this film called Love? in just three days, a film that was a meditation on the nature of happiness (among other things). What is this film called Love? functioned as a kind of creative palate-cleanser for Cousins and, unlike the herculean effort of The Story of Film, was spontaneous, unplanned. A Story of Children and Film (that indefinite article is important) feels, in more ways than one, to be a meeting of the two films, a historiography of cinema through a personal prism, prompted by a chance incidence of home recording.

Image courtesy of the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

The film was inspired by an unplanned recording of Cousins’ niece and nephew playing in his Edinburgh flat one morning and takes its structural queues from the themes he found in this ad hoc footage (and then some). These themes encompass shyness, social class, the strop, enacted parenting, conflict, dreams and adventure (among others). In his distinctive and captivating (captivated, even) Ulster brogue, Cousins leads us through fifty-one films from Denmark in the ‘40s (Palle Alone In The World), Iran in the ‘70s (Two Solutions For One Problem), Japan in the ‘90s (Children In The Wind) and the USA of the current decade (Moonrise Kingdom); his selection encompasses directors as diverse as Bill Douglas, Charlie Chaplin, Ingmar Bergman and Luis Buñuel to explore his chosen themes.

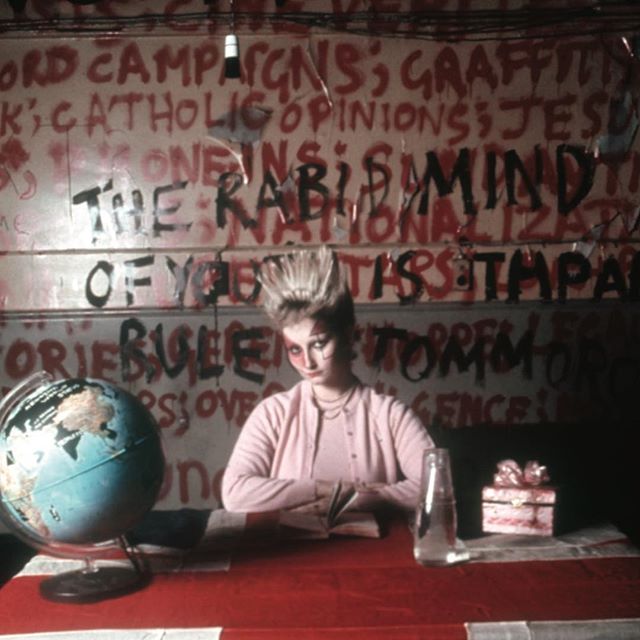

At one point the unnatural (actually somewhat creepy) performance of Shirley Temple in Irving Cummings’ Curly Top is contrasted with Margaret O’Brien’s bum note laden duet with Judy Garland in Vincente Minnelli’s Meet Me In St Louis, Cousins remarks that "We are spellbound by [O’Brien]” – we are, but we’re spellbound by this film too, entirely apposite given its subject; we marvel with childlike wonder at both children in cinema and at cinema itself. This only serves to illustrate and underline the thrust of the film, “Could it be that kids are movies? That the movies are kids?” That would be an eye-rolling moment had these questions come at the end of a film that did not so subtly nudge us towards this conclusion all the way through, and it’s a very convincing argument, beguilingly executed. Cinema in its purest experience is open to the world and open to everyone, everything; it is egalitarian, simple, profound, honest, fantastical - these qualities only get disrupted when adults (or, perhaps, ‘adults’) get in the way.

Andrew R. Hill