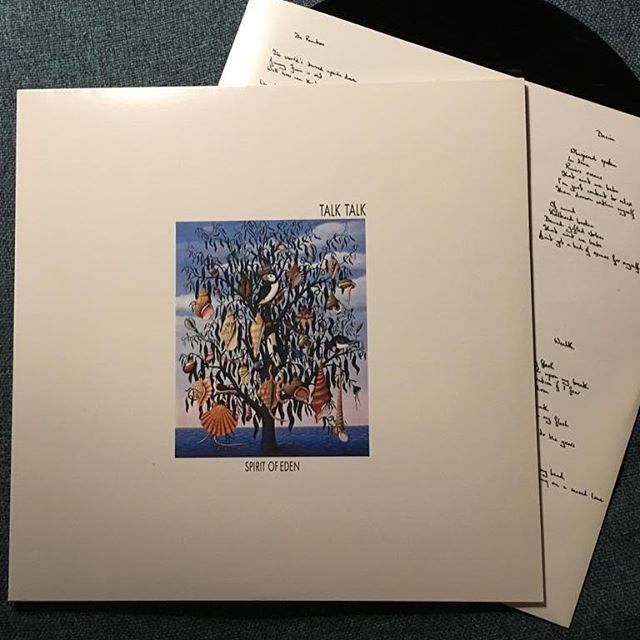

Starred Up - dir. David MacKenzie

Image courtesy of Sigma Films

Eric Love (Jack O' Connell) is a young offender who gets transferred to adult prison due to his hard to control, violent behavior - early on in the film, he earns the designation ' single cell, high risk'. By a twist of fate, his father Nev (Ben Mendelsohn) is also on the same wing......

I must admit I wasn't overjoyed at the premise of David MacKenzie's new film. Even though I am a fan of his solid body of work (including Young Adam and Hallam Foe), I wondered what else there was to add to the prison drama 'subgenre'.

Whilst Starred Up hardly brings anything new to the table, it somehow manages to tell a story that has cliché written all over it (the difficult father-son relationship, the generous but misunderstood counsellor, the corrupt prison guards) in a fresh, and ingenious manner. Yes, it is 'gritty', and yes, it tries to be 'authentic' with his handheld camera shots and 'real' location (a disused Belfast prison), but it also portrays characters that are anything but one-dimensional and that remain largely unknowable. Eric, his father and the rest of the inmates go beyond the good vs bad distinction that is usually a staple for this kind of film. Their behaviour is largely erratic and unpredictable. Similarly, counsellor Oliver (Rupert Friend) is well-meaning, but clearly has some issues of his own. Is his interest in Eric just limited to his job requirements? Questions like this are not met by easy answers: the dialogue is kept to a bare minimum, and is often simply hard to understand. The cast seem to communicate in an almost primitive way. Of course, this could be a consequence of living in an environment that is clearly dehumanising, but it also gives an impression that we are witnessing a story that is interested in human nature in its most basic form. The images on screen seem to confirm this impression: every burst of violence is carefully choreographed, and takes on a meaning that goes beyond the immediacy of the action. The film's 'naturalism' is clearly not what it superficially appears.

Starred Up ends with a shot of a revolving door (a recurrent image throughout the film): it left me wondering whether this is simply a nihilistic reference to the never-changing nature of the British prison system or more of a reflection on the vicious circle that violence often produces.

Erika Sella

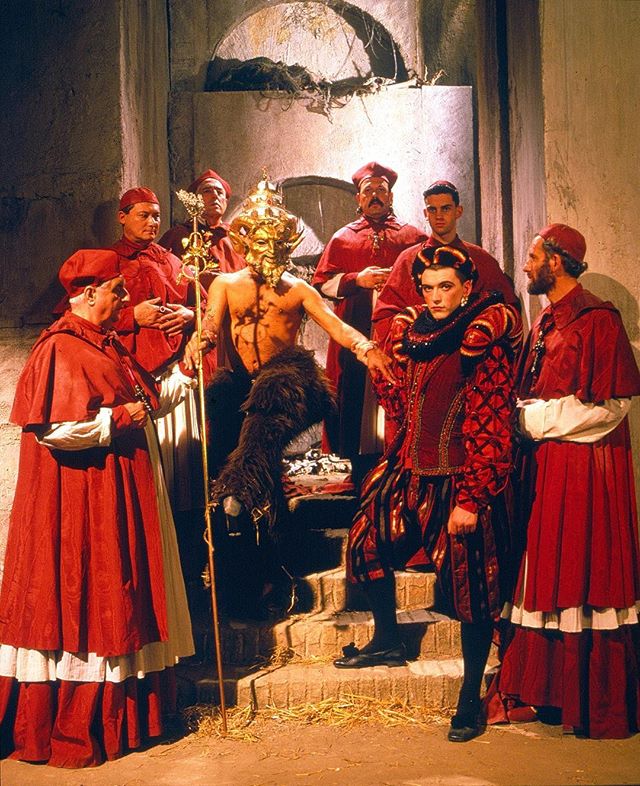

The Strange Colour of Your Body's Tears - dir. Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani

Image courtesy of BFI

Who doesn't love a Giallo? The last decade seems to have brought a massive revival for the 60s/70s Italian 'genre', Glossy DVD releases, conferences at film festivals, academic books, countless website and blogs, and Berberian Sound Studio.

Cattet and Forzani are clearly fans, as this is their second venture (after 2009's Amer) that heavily references this source material. The Giallo semiotic staples are all there: a killer with black gloves, plently of female nudity, the 'groovy' soundtrack, the Art Nouveau building (heavily reminiscent of the dance school in Suspiria), At one point, there is a very direct nod to the much-loved The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh as the protagonist 'enjoys' a sexual encounter involving shattered glass.

The Strange Colour of Your Body's Tears should not be judged on the basis of its stick-thin plot (a man trying to unravel the mystery of his wife's disappearance) - beyond its excessive cinematography, and its very core, it is not a giallo, (in many of the Italian thrillers, scripts were convoluted and often nonsensical, yet fundamental part of what made them enjoyable), but rather something more akin to early Buñuel or to Jodorowsky. Yet, despite its art house aspirations, this film is an overall fail: very quickly, its 'cinema of attractions' strategy (a cavalcade of kaleidoscopic effects, split screens, blinding primary colours etc. ) appears thin and tiresome, leaving the viewer with very little to get stuck in.

The general impression I was left in was that of an over-long, humorless and very pretentious music video. A real shame seen that the filmmakers' attempt to breath new life into a still underrated genre is a valiant and worthy one.

Erika Sella

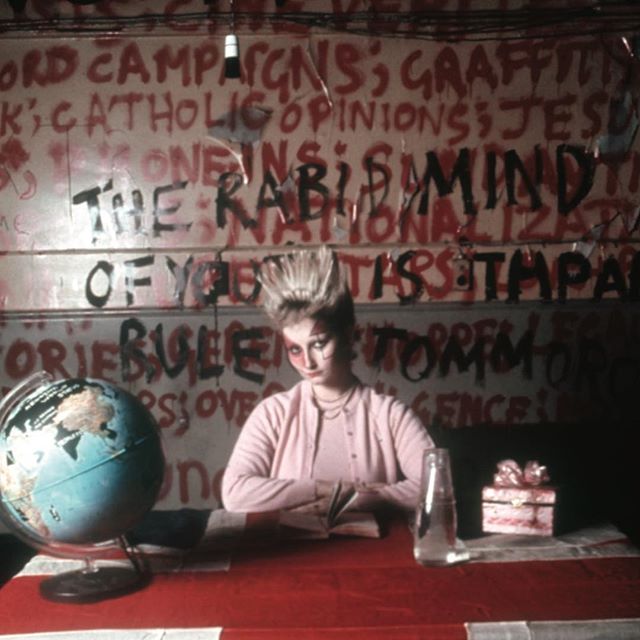

Of Horses and Men - dir. Benedikt Erlingsson

Image courtesy of Icelandic Film Centre.

Benedikt Erlingsson's Of Horses and Men is a funny, brutal, humane, charming film that looks at the lives of a rural community through a series of interlocking vignettes. Unsurprisingly, horses feature heavily and are central to the characters' stories, livelihoods, romances, misadventures and (in a couple of cases) deaths. The backdrop might be so barren as to border on the lunar but warmth permeates throughout, even at its most shockingly violent junctures (which are often immediately preceded by comedy that borders on the slapstick). As with the lives of these characters (their stories, their horses), the comic and the tragic interweave, are rarely far removed from one another; it is an approach that was always bound to endear the film to to a Scottish audience - the two are practically inseparable here, after all.

Of Horses and Men is a deftly executed, uplifting set of stories that looks at the characters relationships with their environment, the animals on which they rely, and each other, without ever piling on cloying sentimentality - impressive given that horses seem to be afforded a particular status that few other animals are (cf Findus lasagne-gate 2013, War Horse, etc.). The same night the film was presented at the GFF, the film did very well at the Edda Awards, the 'Icelandic Oscars'; it's unsurprising the myopic, increasingly irrelevant American equivalent overlooked a film of such wit and depth (the film was Iceland's - ultimately unselected - entry to this year's Academy Awards Best Film in a Foreign Language category) - this film sees no need to make sweeping commentary on Life. Its specifics relate to a way of life that is obscure to many, probably most, and yet this specificity creates a universality with which one can identify and enjoy without resorting to trite overstatements - it has subtleties far-removed from the majority of the string-laden statue-bait. Unfortunately, it's likely to be a case of 'catch it if you can' rather than 'while', but the sentiment remains the same.

Andrew R. Hill