When Eyes Without a Face (Les Yeux Sans Visage) was presented at Edinburgh Film Festival in 1960, seven audience members fainted, prompting his French director, Georges Franju, to caustically remark: 'Now I know why Scotsmen wear skirts'. The film scandalised audiences around the world, and it nearly cost a job for a dissenting English critic who admitted she rather liked it.

What was the reason behind such an extreme reaction? It might partially be justified by film's infamous sequence of facial removal surgery – even now, 45 years later, the prolonged nature of these scenes, complete with an obsessive and extremely precise fascination with medical procedure and surgical paraphernalia, can make a viewer feel queasy.

Perhaps the scandal was also due to the stature held by Franju up to that point – how could such a serious and socially committed artist (who, along with Henri Langlois, was behind the Cinémathèque Française) debase himself by working with a lowly genre such as horror? In truth, Eyes Without a Face is hardly a gory horror film: cleverly infusing elements such as pulp, noir and melodrama, it quietly disturbs and unsettles – 'a film of anguish' as Franju himself once said.

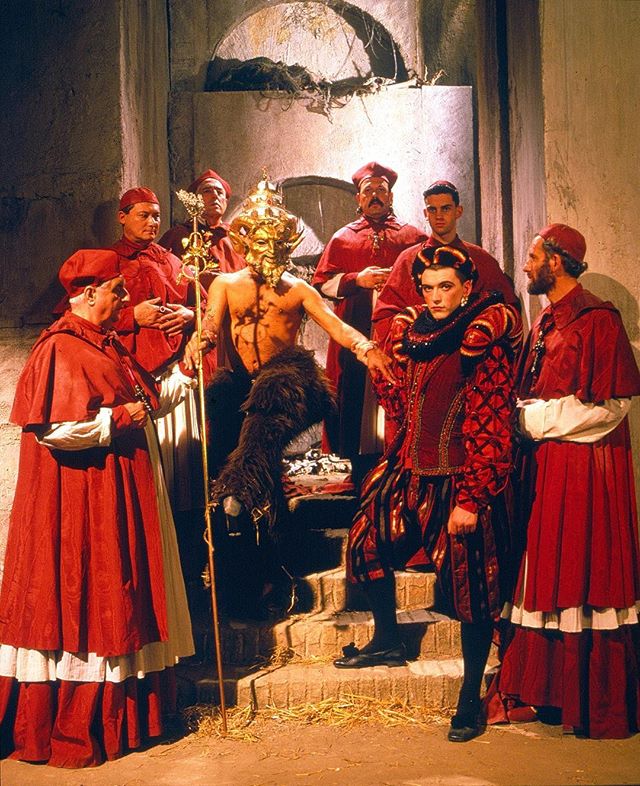

The opening sequence, visually reminiscent of Jean Cocteau's work, sees an attractive, middle-aged woman driving a battered Citroën 2CV down a stretch of eerily lit road. She appears tense, and it's soon clear why: a crumpled, sinister figure wearing a long trench coat and a hat is in the back seat. The woman eventually gets out of the car to dispose of what is clearly a corpse. We will soon find out that this woman is Louise (majestically played by Alida Valli), the loyal assistant/secretary and perhaps lover of pioneering 'heterograft' (tissue transplant) surgeon Dr Génessier, whose daughter Christiane has gone missing in mysterious circumstances. Or has she?

Christiane is actually imprisoned in her father's labyrinth-like mansion, hideously disfigured from a car crash that was caused by her father's reckless driving (at one point, she remarks that he was driving like 'a demon'). Tormented by guilt and driven by selfish scientific drive (and perhaps genuine paternal love), Dr Génessier reassures his daughter that she will have a real face again, while reminding her to wear the plain, white mask that hides the missing facial tissue. Of course this comes at a tragic cost – young women and tracked down and kidnapped by Louise, their faces carved out by the surgeon's confident scalpel, and grafted onto Christiane's.

With such a set up, it would have been easy for Franju to follow well-known stereotypes: the evil/mad scientist, the loyal assistant, the beautiful daughter imprisoned in a large, fairytale-like house. Clearly not interested in a simple good/evil dichotomoty, the French director weaves a subtle, painful and slightly perverse web in which the everyday and the monstrous comfortably coexist.

Tonally, the film's quiet, almost dreamy pace and luminous cinematography give the subject matter a surreal character rather than a horrifying one. In Franju's world, nothing is as simple as it first seems - Génessier is undoubtedly crazed and immoral, but he is not simply heartless: we see him being kind to a young child and his mother at the clinic he works in. His assistant Louise is complicit in horrible murders but is often shown as troubled by her actions and as caring towards Christiane. The latter might be the agent to the film's ultimate resolution - and the one character that is clearly as symbol of goodness and purity (she is associated with doves and often wears floating, white robes) - but she also fails to release a victim that is about to be operated on as she still hopes her father will succeed in reconstructing her face.

Eyes Without a Face is a complex poem that resists straightforward interpretation, a reflection on identity, and what it means to be human (or inhuman), as well as a comment on the limits of science. Above all, it s ultimately a very satisfying film experience - seek it out.

Eyes Without a Face will be released on dual format edition DVD/Blu-Ray by the BFI on Monday 24 August. Packed with amazing extras such as a feature-length audio commentary by Blasted favourite Tim Lucas , short films by Franju, a documentary on the French director, and an interview with Edith Scob (who plays Christiane), it also comes with a fully illustrated booklet. The film has been remastered in high definition, and it truly is a visual feast.

Erika Sella