Reel Gone looks at films that we think should receive more exposure and critical attention. It's essentially an excuse to write about things we like, even if they haven't been recently released on DVD or shown in cinemas.

Even if it sits at number 83 in the BFI Top 100 British Films list (and brought Julie Christie an Academy Award win for best actress), John Schlesinger's Darling (1965) is still a bit of a lost classic. Not as loved or even well known as the exuberant and highly inventive Billy Liar (1963), it was dismissed by its own director with some pretty damning words - "It's far too pleased with itself. I wince when I see it now".

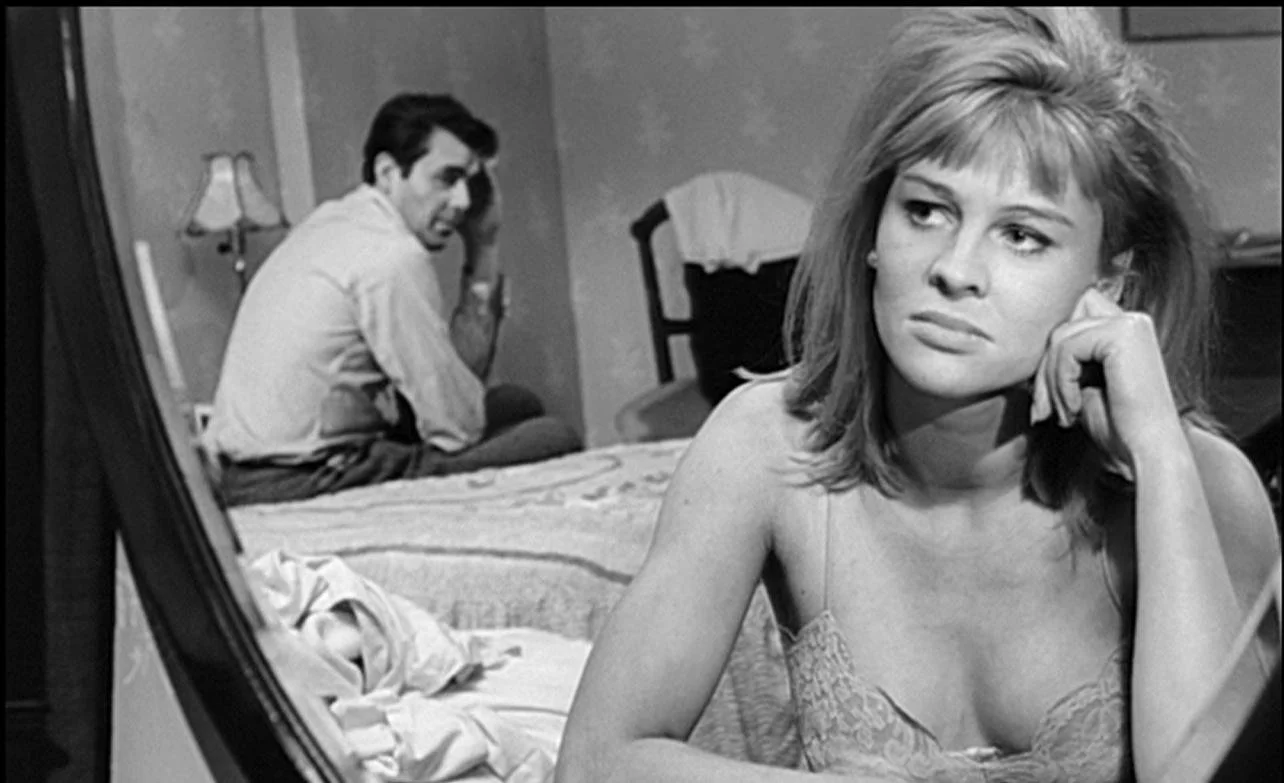

A glass world - Julie Christie and Dirk Bogarde in Darling

The film is often reduced in much literature to a somewhat stuffy and dated tale about the 'rise' of an amoral model that sleeps her way to the top of the Swinging Sixties London Scene. Superficially, the story of provincial beauty Diana Scott might indeed appear as a didactic, almost cynical Hogarthian analysis of the woes brought about by the consumer revolution: the disregard for the traditional values of marriage, motherhood and monogamy results in resigned despair for our protagonist. However, as in Lewis Gilbert's Alfie (1966), our judgement is coloured by the often unreliable first-person narration (in an interesting move, the film mimics the structure of a tabloid article - it opens with Diana telling 'her story' to a woman's magazine), and by the protagonist's youthful vivacity and undeniable charm.

Ephemeral joy - Robert and Diana become lovers

Darling constantly walks a fine line between exuberant celebration (the scene that sees Diana and her lover Robert move in together, the Italian vacation photo sequence) and razor-sharp satire (the charity ball shows up the London elite as vulgar, hypocritical and racist). In equal measure, Schlesinger seems ambivalent towards his protagonist: is Diana really a manipulative and calculative starlet, or simply a misguided victim of circumstance?

The face of a model - Diana Scott

Diana certainly has something in common with Liz, the character Julie Christie played in Billy Liar: young, hip and carefree, with very little time for convention. Schlesinger even goes as far as introducing both with very similar sequences - handheld shots of Liz/Diana walking in the street, smiling, swinging her handbag. But whereas Liz represented the possibility of escape from the drudgery of everyday life, Diana becomes the emblem of what happens when those fantasies become all too real: she does arrive in London, she meets and interacts with journalists, artists, directors, and even aristocrats, but is ultimately disappointed by a life that doesn't live up to her expectations. A bit like Flaubert's Emma Bovary, she dreams of becoming sophisticated and cosmopolitan, but faced with harsh reality, she easily gives up on her aspirations.

Beauty as commodity - Diana and Robert

She starts pursuing a career as an actress, and attends an audition. She soon realises that her small role in a trashy horror film is no match for the kind of experience the other would-be thespians all seem to have, and she quickly abandons her attempt to go and sleep with Miles (a cynical advertising executive) instead. While this sequence might seem a little preachy (and maybe what Schlesinger was referring too when he said he found the film too 'pleased with itself'), it clearly show disappointment at what the new age of 'liberation' really means: a woman still needs to sell herself in order to succeed - deprived of a certain kind of education (she is seen in opposition to Robert, the intellectual, who clearly doesn't take her ambitions (or her frustrations) very seriously). A symbol of times that should have brought emancipation and real development, but instead only ended up mimicking old structures and gender relations, Diana is in essence a commodity - she can only have access to a rarified, sophisticated world through the way she looks. Clearly the consumer revolution has only brought on a different kind of subjugation for our protagonist. In this sense, Darling has got plenty in common with another 'hidden gem' of the era - Jerzy Skolimowski's Deep End (1969), a film that sees an attractive young woman failing to to become the master of her own destiny after she becomes a plaything for a coarse fiancé, an abusive former teacher and eventually a younger colleague. But where submission to a certain social order meant physical death by spurned lover for Jane Asher's Susan, it simply delivers heart-breaking resignation for Diana.

The sad princess.

Condemned to a world of aristocratic formalities by virtue of a loveless marriage, she discover her dreams have turned sour. In a memorable scene, Julie Christie gives notable emotional depth to her character, who in despairing fury, strips off her clothes and destroys the ornate draperies of the mansion that has already become a cage.

In a lesser director's hands, Darling could have been a cack-handed morality tale for Daily Mail readers. Thankfully it isn't - playing on the charm and ability of its lead actors (Dirk Bogarde is resplendent in the role of the unsatisfied, repressed intellectual), and having a lot of masterly fun with its medium, Schlesinger interrogates the viewer on matters that are as relevant today as they were in 1965 (Diana Scott could be any of the model-cum-actresses that fill the pages of Glamour or Hello magazine). With its explicit depiction of casual sex, infidelity and abortion, it isn't perhaps as shocking now as it was in 1965, but as a story of a highly intelligent yet fickle and elusive woman failing to find happiness (after all, its director is fixated with losers), it remains something worth watching again and again.

Erika Sella