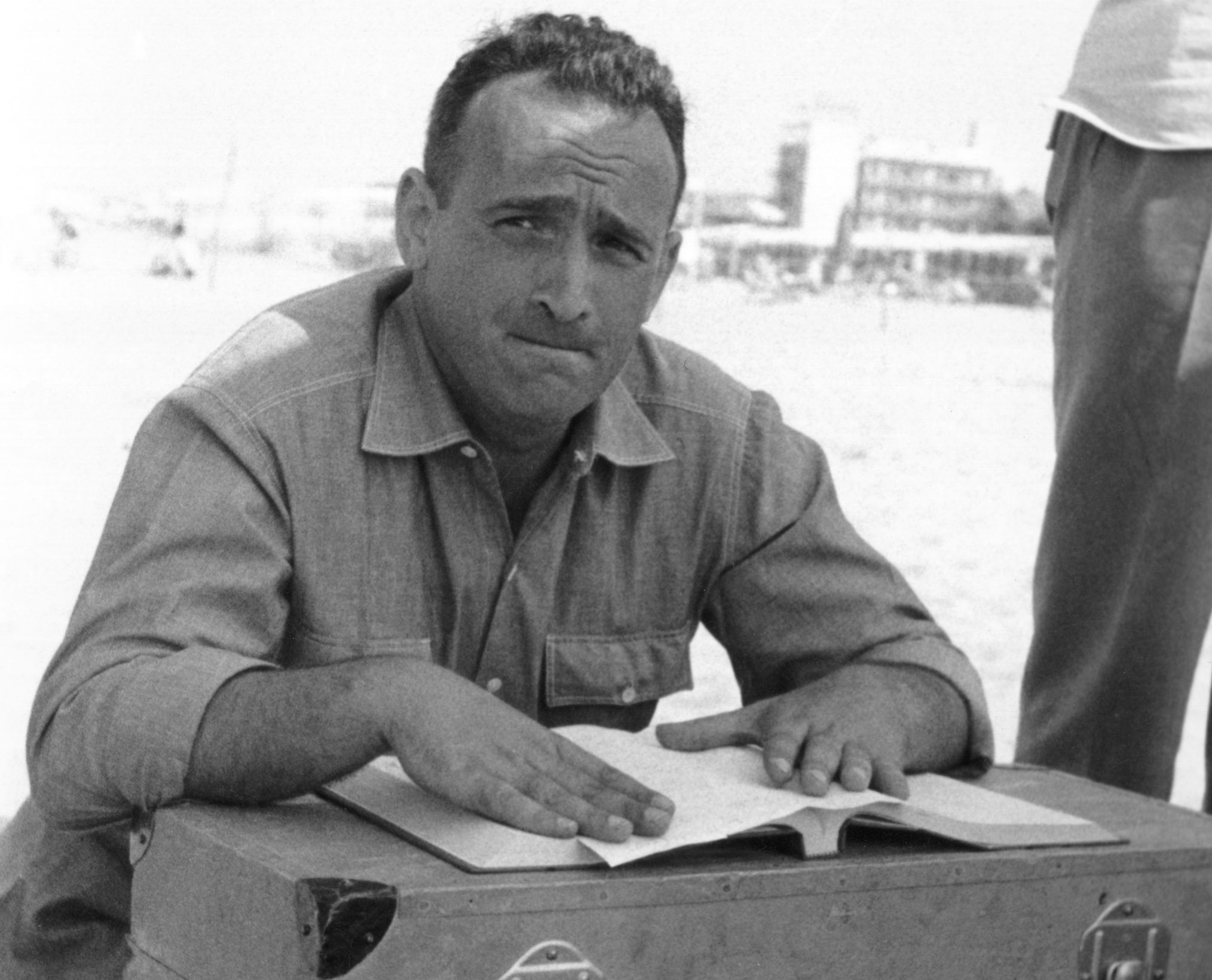

Valerio Zurlini is one of the most criminally underrated directors of all time. Born in Bologna in 1926, he studied law, and later art and painting, before working on a number of short films and making his feature debut with The Girls of San Frediano (Le Ragazze di San Frediano, 1954).

Valerio Zurlini

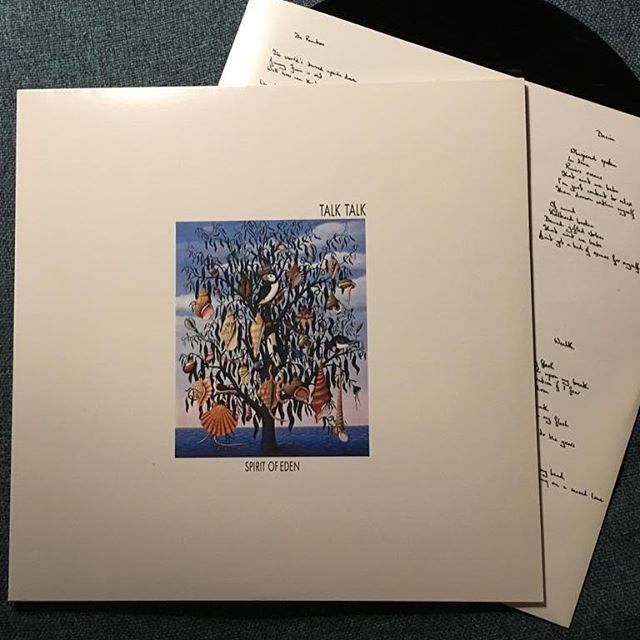

In his tragically short life (he committed suicide in 1982), he made eight intense and beautifully austere films, his career ending with a stunning adaptation of Dino Buzzati's The Tartar Steppe (1976). Most of Zurlini's work is relatively hard to see nowadays, the only recent major DVD release being No Shame's 'The Valerio Zurlini Box Set: The Early Masterpieces', a remarkable outing that contains both Violent Summer (Estate Violenta, 1969) and Girl with a Suitcase (La Ragazza con la Valigia, 1961). The latter was shown at the Glasgow Film Theatre back in 2008 and was my personal introduction to the director's work - a film that had me in tatters.

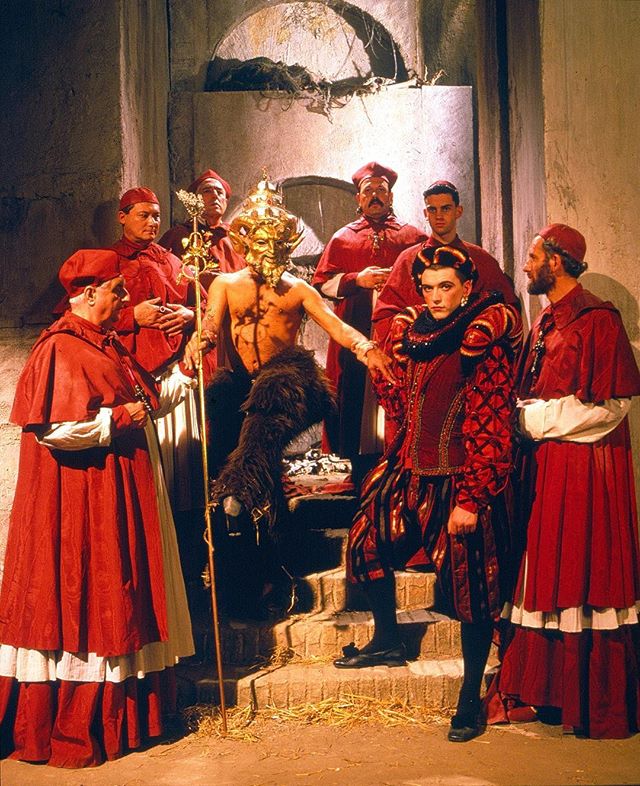

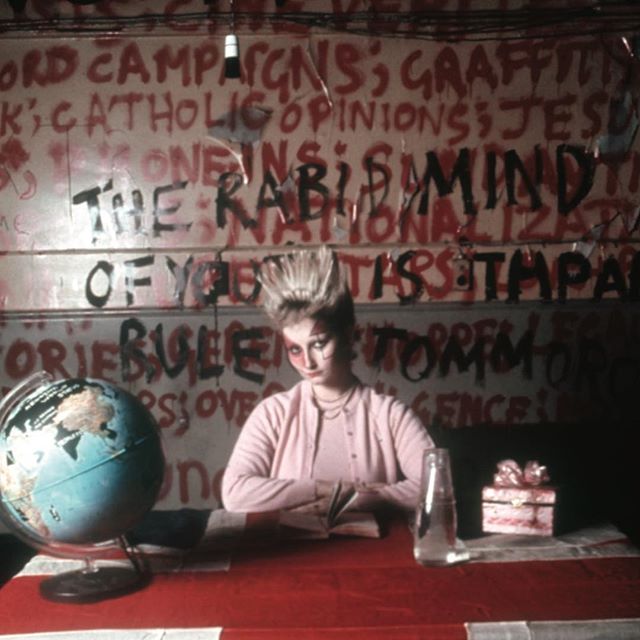

Girl with a Suitcase is the story of a doomed 'brief encounter' between Aida Zapponi (played by Claudia Cardinale), a twenty-something would-be nightclub singer, and Lorenzo Fainardi (Jacques Perrin), a shy and naive upper class teenager. From their early, awkward meetings, the two make a connection despite the respective milieux keeping them apart - Aida, dirt poor and condemned by her own coping strategies, Lorenzo imprisoned a bourgeois ivory tower carefully run by his stern and undemonstrative aunt. The film is an interplay of a high culture/low culture dichotomy: popular hits of the day (Mina's 'Il Cielo in una Stanza', Peggy Lee's 'Fever') mix with opera (Verdi's aria 'Celeste Aida') as we travel from a rarified Parma, home of mansions and grand, crumbling museums, to a the livelier seaside resort of Riccione, a town seemingly populated by penniless musicians and sleazy chancers.

Aida is earthy, wild, street-wise and yet extremely vulnerable: when she first approaches Lorenzo (she is looking for his brother Marcello, who has cruelly ditched her), she goes from detached scheming (she pretends she works for an insurance company) to quiet desperation in a matter of minutes. She's been hardened by what life has thrown at her, but retains an unshakeable innocence. We first see the couple standing on the steps of the Fainardis' imposing home, Lorenzo descending the steps to reach out to this complex creature from a world unbeknownst to him, his expression a mix of tenderness, pity and longing. The scene has a dreamlike, painterly quality to it, the protagonists' long, dark shadows dominating the screen: it's almost as Zurlini wants us to be aware that this is not a union that can exist in the real world.

Lorenzo idealises Aida and innocently uses his wealth to try and help her situation and keep her close to him: he lends her 5,000 lira, puts her up in a local hotel and, when she feels that her 'rags' are not suitable for eating dinner amongst the resident well-to-do, he even buys her an expensive dress. Slowly, reality starts creeping into their relationship, and Lorenzo begins to realise the unbridgeable gap that exists between their worlds. The gradual process begins when Aida, not one to pass on a free dinner, gives into a rich hotel guest's cajolery, and ends up dancing with him. While 'El Degüello' (a declaration of war, if ever there was one) plays in the background, Lorenzo sits silently in the mid-distance observing the scene, his young, slightly emaciated face expressing rage, jealousy, disappointment, yearning. Girl with a Suitcase is worth seeing for this scene alone, as rarely such high drama has been so masterly underplayed: the film's power lies in its refusal to allow its material slip into cheap melodrama. Emotional punches (there are many) are delivered through things glances, gestures, and what is left unsaid.

In my eyes, Zurlini remains unmatched in depicting lonely, lost individuals that try and make sense of the uphill struggle that is their existence. But for all its bleakness, Girl with a Suitcase is a celebration of those moments that make life worth living. Take the scene at the beach, with Lorenzo and Aida finally locking in an embrace that expresses more solidarity and understanding than carnal passion - there is so much intensity on the screen that you almost feel like you have to look away. To put it mildly, in its handling of sentiments and of what makes us human, this film is nothing short of miraculous - seek it out.